Digging into history of New York’s use of plants

I am constantly amazed at the variety of topics for this column that just fall into my lap. Recently, I attended a lecture about Anton Kerner von Marilaun – Austrian botanist and professor at the University of Vienna. Professor Kerner was interested in phytogeography – “the geographic distribution of plant species and their influence on the earth’s surface” – and, not surprisingly, phytosociology – scientific discipline that deals with “plant communities, their composition and development, and the relationships between the species within them.”

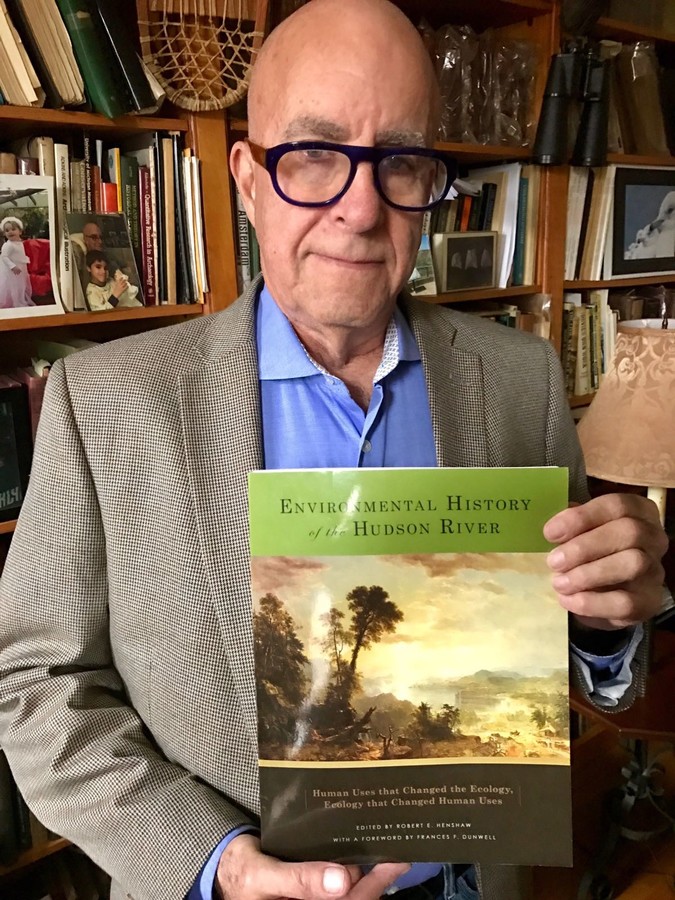

I chanced to speak with another of the attendees, Joel Warren Grossman, an Andean and North American archeologist, who manages and directs excavations at challenging archeological sites in North and South America. It turns out that he is a contributor to the volume Environmental History of the Hudson River published in 2011. He wrote Chapter 8, “Archeological Indices on environmental Change and Colonial Ethnobotany in 17th Century Dutch New Amsterdam.” The 45-page article first reconstructs the archeology and colonial history of the Dutch West India Company block and then reconstructs the changing plant diversity between the 17th and 18th centuries. And to top it off, he lives in Riverdale!

Archeology is not simply for far-away exotic locations whose populations have disappeared and whose buildings have been buried by jungles or sand. In fact, Manhattan was already visited by the Frenchman Giovanni da Verrazzano – who explored the Atlantic Coast of North America between Florida and New Brunswick – in 1524, and was first settled by the Dutch in 1609. The famed purchase of Manhattan Island for $24 worth of beads is referenced by a letter written by Pieter Schagen on Nov. 5, 1626 (http://www.lettersofnote.com/2011/07/sale-of-manhattan.html). Much of that transaction remains murky, including who the actual sellers were, whether beads were actually involved, and whether $24 – instead of $1,000 – was the actual amount. Quite a steal regardless. In any case, with more than 300 hundred years of European-style building and living, there are treasures to be discovered buried under the streets, particularly those of Lower Manhattan.

And so, in 1984 the New York City Landmarks Commission – established in 1965 in response to the loss of the Beaux Arts Pennsylvania Station that was demolished in 1963 – mandated the excavation of a section of Pearl Street, which fronted on the waterfront – known as the Strand – to a depth of 8 feet to 12 feet below the current streets. Joel W. Grossman, Ph.D., was hired to first develop a map-based sensitivity assessment and then an excavation strategy to expose and document the buried colonial city of New Amsterdam. His interests here include ethno-botanical samples and what we can learn about the human use of plants. The excavations covered three periods: 1) 1630-1650, Dutch culturally, 2) 1680-1700, Dutch culturally, English politically, 3) 1710-1730+, completely English.

Using well-established archeological techniques, samples of earth were taken from 26 different locations where the time period could be determined. After thorough washing, 1,458 seeds identifiable to the genus level were collected for a total of 24 types. Of these, 19 separate genera come from Period I, 13 from Period II and only 5 from Period III. The different varieties that show up as environmental time capsules in the different strata and features (cisterns, wells, pits, beam slots, foundations) are interesting. The colonial block (ca. 1633-1650) may have had a medicinal garden. Dr. Hans Kierstede (according to early documents, he maintained a medicinal garden in the block) and his wife – well-known herbalist Sara Roelofs – lived on the block. Sara grew up in regular contact with local Indians and spoke fluent Algonquin. She also used the Indian women as informants in matters of native medicinal remedies in the same manner that the botanists of the Dutch East and West India Companies who routinely sought out indigenous women to learn about local medicinal plants.

Plants that are characterized as indigenous potherbs (“a plant whose leaves, stems or flowers are cooked and eaten or used as seasoning”) and starchy food sources – with possible use as medicinal plants were found solely in the early 17th century and then disappeared. Those plants include amaranth (Amaranthus), lambsquarters (Chenopodium), knotweed (Polygonum), purslane (Portulaca), tobacco (Nicotiana), bedstraw (Gallium), and pokeweed (Phytolacca). There were also seeds of native squashes, peaches (Old World origin) strawberries and raspberries/blackberries.

Late 17th century shows purslane, members of the cabbage family (Brassica) which are of European origin, strawberry, raspberry/blackberry, peach, and Cyperus (a native sedge with starchy, edible roots).

Early 18th century sees a great reduction in plant diversity. We suddenly see grape seeds and we continue to see native squashes, strawberries, raspberries/blackberries, and peaches.

Next week’s article is an amazing segue fro botany of 300 years ago.