From a medical perspective, Obamacare seems smart

Right now, 48 million Americans lack health insurance —that is more than 15 percent of us — and many more could lose their coverage in a blink.

Without access to healthcare there is no preventive care, and illness goes untreated until it becomes very serious, so it is no surprise the uninsured have a 40 percent higher risk of death.

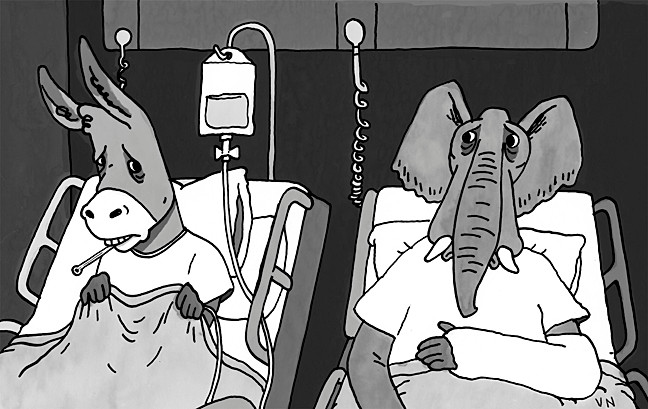

Since the majority of us consider this much needless pain and suffering to be unacceptable, Congress passed into the law the Affordable Care Act (ACA), widely known as Obamacare.

Opponents of expanded coverage ignore these facts.

In 2007, President Bush said, “People have access to health care in America. After all, you just go to an emergency room.” Last year, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney said much the same thing. But, as a physician, I would much rather treat conditions like hypertension and diabetes in the office than treat their preventable and expensive complications, like stroke, heart attack and kidney failure in the hospital.

Obamacare started successfully by extending child coverage to age 26 and eliminating co-payments for preventive care like colonoscopies.

Next, the ACA further expands access by creating so-called insurance marketplaces, outlawing denial of coverage for pre-existing conditions, and offering federal money to states for expanding Medicaid just above the poverty line.

The marketplaces are private insurance exchanges that offer new individual coverage options to millions who do not qualify for public insurance, such as Medicare or Medicaid, or employer-based group plans, with subsidies for low-income families. The new plans are more affordable than ever and consumer interest is high.

However, people should check for participation of their preferred doctors and hospitals. Insurers reportedly plan to profit by cutting provider fees and by excluding some doctors and facilities, including big medical centers, which tend to offer the most advanced care.

One of the most controversial parts of Obamacare is the individual mandate, under which people must pay a fee if they decline to enroll in a health plan.

That might sound crazy — some critics have called it a “violation of our sacred freedom” — but the logic is clear. To prohibit denials for pre-existing conditions while keeping health insurance affordable, everyone must participate. Otherwise, healthy people would be tempted to stay out of the system until they need it, and these “free-riders” would make coverage truly unaffordable for everyone else. This is like how we support our local police and fire departments – you don’t just pay the police if you’ve been robbed! If enough healthy people enroll, the marketplaces should work, except that we may run into a sudden shortage of primary care providers.

The biggest objection to expanding coverage is the cost. We have an aging and not very healthy population served by the world’s most expensive healthcare system. Medicare’s finances are stretched and Medicaid is already straining state budgets. Many conservative states are resisting Obamacare by declining federal funds for Medicaid expansion, while others like Florida are paradoxically handcuffing their own marketplaces. This is happening even though the insurance exchanges will only offer private insurance, without the public option of competition from a Medicare-like federal plan, which liberals badly wanted.

To cut costs, Obamacare offers several measures.

Since traditional fee-for-service medicine can promote overutilization, there are new patient care models that emphasize quality over quantity and reward efficiency. Medical societies like the American Medical Association generally support these initiatives and are boosting their own efforts to rein in unnecessary care through programs like Choosing Wisely.

However, many doctors are frustrated about mounting pressures and there are some pitfalls.

For instance, the methods required to define efficient care are very complex. If they are not accurate, they may unfairly penalize practices that treat poorer or sicker patients, whose care costs are more expensive.

Healthcare costs must be contained, but putting the onus on doctors will not solve all our problems.

We could trim more costs by promoting healthier lifestyles, reform guidelines for malpractice suits, and encouraging end-of-life planning, which should be bipartisan issues.

Still, if we want better care than Mr. Bush’s Emergency Room Health Plan, we need to pay for it. I don’t see a problem with added taxes on cigarettes, sugary drinks and junk food, so that people contribute more to the future societal costs of their free choices.

After things settle down, the focus should shift away from overturning the law and all of us should start working together on further improving our health and health care.

Dr. Gerry Neuberg is a cardiologist at NY Presbyterian Hospital and a Professor of Medicine at Columbia University, with a practice in Riverdale.