An anomaly or the norm — Muslim feminists speak out

Growing up, Sarah Alsaidi would introduce herself as Sarah, without any of the Arabic pronunciation her Yemeni parents originally accented it with. At home, it’s not “Sare-AH,” but instead “Sah-RU.”

Yet, because of her hijab and dark eyes, Alsaidi still encounters people who add their own Arabic flair to her name, mispronouncing it “Sahara,” after the desert even when she says it in an American tone.

“There is that assumption that it has to be something exotic,” Alsaidi said. “Growing up, I wanted to fit in and I pronounced my name with out the accent. But I’m at a point in my life where I just want to be myself.”

Alsaidi, a doctoral student in the counseling psychology program at Columbia University, is both a Muslim and feminist. To her, the two are never mutually exclusive.

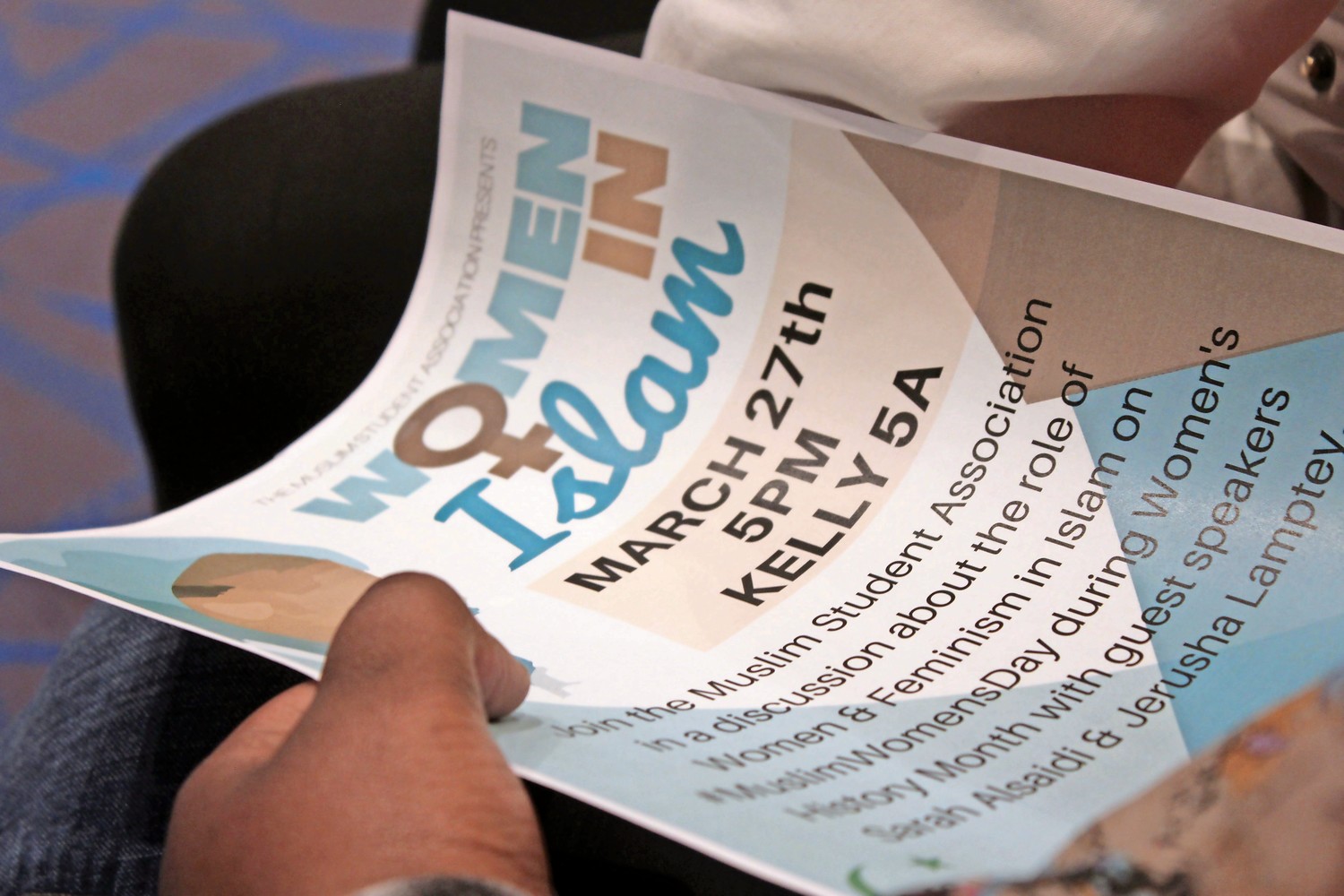

Alsaidi shared her research on mental health when it comes to Muslim Americans during a recent panel at Manhattan College. Alsaidi saw it not just as an opportunity to share her research, but also to validate the experiences of young Muslim women by letting them know she’s been through all of it, too.

In some Yemeni households, women are encouraged not to pursue education past high school. But Alsaidi’s family was nothing like that, living by the Muslim hadith, “Your heaven lies under the feet of your mother.” While that prompted many in her family to not stymie pursuing dreams because of gender, there were others who simply couldn’t see past stereotypes and chose to believe Alsaidi faced persecution at home.

The panel was hosted by the Muslim Student Association and was inspired not only by women’s history month in March, but those very beliefs that MSA president Rabea Ali noticed were present at Manhattan College.

“The whole general concept of women rights in Islam is being misconstrued in the world and being blown out of proportion,” Ali said.

Judgment like that can be damaging, she said, especially when other groups attempt to speak for the rights of Islamic women — like what happened at the Women’s March held last January.

“It seemed like it became a white Women’s March and something for white women to put forth their agenda,” Ali said. “That’s where I feel apprehensive, and I think that the voices of color are being shut down.”

Jerusha Lamptey, an assistant professor of Islam and ministry at Union Theological Seminary at Columbia, talked about how media regularly shows Muslim women as severely oppressed.

“In many people’s expression of concern, they erase the agency of Muslim women and the humanity, and they speak for us instead of speaking to us,” Ali said. “When it comes to feminism and Islam, people need to not look at the propaganda and look at the religion and talk to Muslim women and see how Islam is exhibited in their lives.”

Far too often, the media, she says, pairs religion with culture, especially when it comes to the portrayal of Muslim women. One example is the driving ban in Saudi Arabia where people see the law based on religion rather than what is simply the culture of the country.

“People consider Saudi Arabia to be the epitome of Islam, which is just not true,” Ali said.

Islam’s religious values are separate from laws of countries, including views on women’s rights. In Islam, based on Ali’s interpretation of the Quran, freedom and respect are never rights denied to women.

She cites a verse in the holy book that says “it is not lawful for you to inherit women by compulsion. And do not make difficulties for them in order to take back part of what you gave them, unless they commit a clear immorality. And live with them in kindness.”

Melanie O’Connor attended the discussion based on the work of her own group, Nur, a student-led initiative that combats Islamophobia.

“I think that it’s really important for people to understand a lot of people,” O’Connor said. “People think that feminism is just one way, and there are a lot of different ways for different people.”

After the discussion, some girls approached Alsaidi expressing their gratitude for what she shared. One student even encouraged her to keep using the Arabic pronunciation of her name.

“If you ask 17 different Muslim women about Islam, you’re going to get 17 different answers,” Ali said. “And that’s kind of the best part about Islam. It’s diverse.”