Black power exhibition takes visitors back to turbulent times

Make black count.

Support black liberation — Free Assata Shakur, Free Sundiata Acoli.

African Liberation Day.

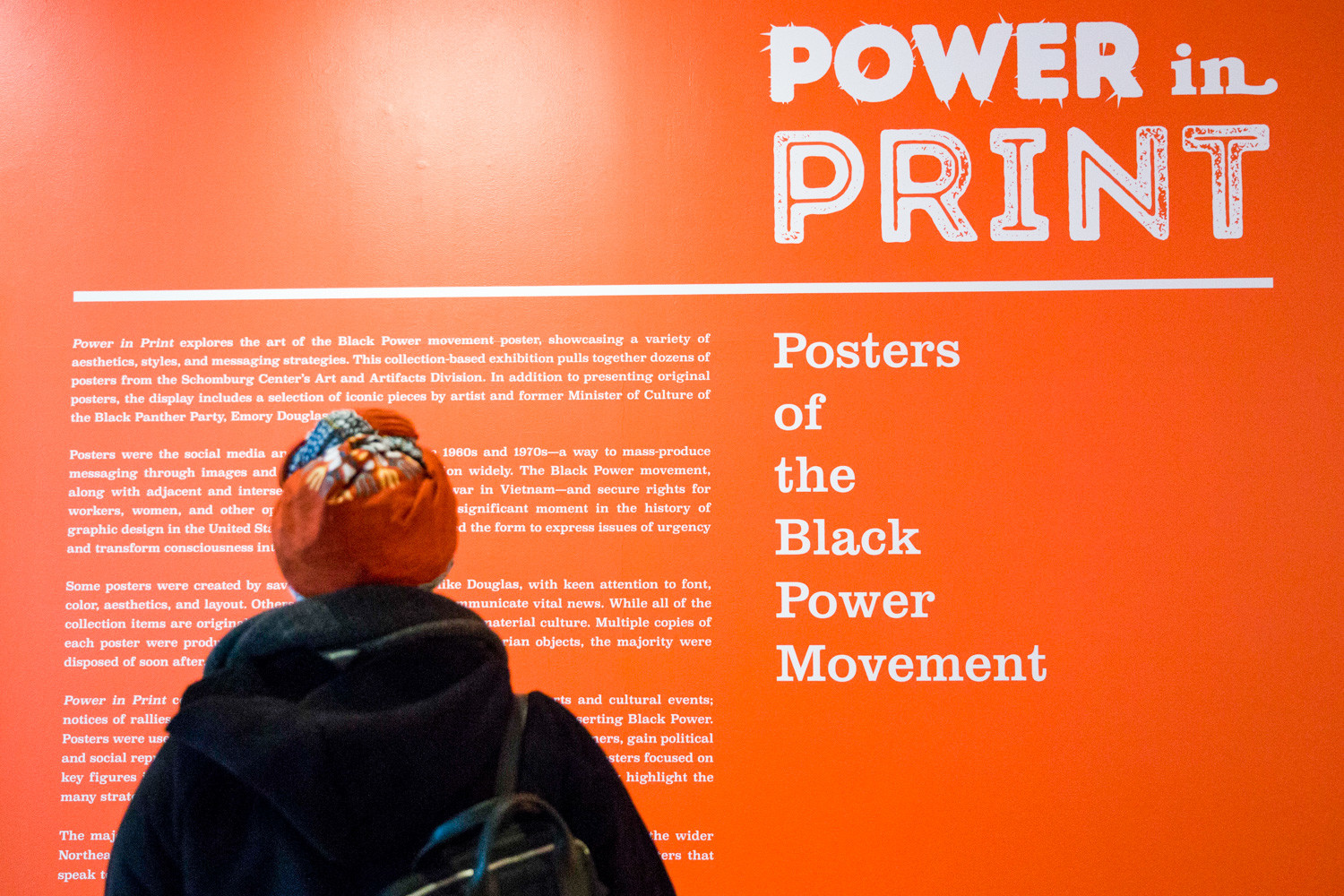

With posters like these, the mood of the black power movement comes to life in the “Power in Print” exhibition at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. The show, which runs through March 31, explores the art of the black power movement through its posters.

The term “black power” was a concept and call to action as African-Americans fought against racial oppression, urged economic self-sufficiency, and pushed schools to add black studies courses during the 1960s and 1970s. The movement also encouraged blacks to dress in African-inspired clothing and wear Afro-styled hair, embracing their cultural heritage.

“The black power movement spread like wildfire when Stokely Carmichael coined the slogan in 1966,” said Mark Naison, a history and African-American studies professor at Fordham University. For younger African-Americans — both in their communities and in college — it was a dramatic change in how people organized politically and how they represented themselves.

“When integration was the proclaimed goal, middle-class African-Americans went out of their way to dress the way middle-class white Americans presented themselves,” Naison said. For example, men attended sit-ins dressed in ties and jackets, and no one wore large Afros in the early or mid-‘60s, he said.

“By 1967 and 1968, people grew their hair out,” Naison said. “Many of them started wearing African garb or started wearing black leather like the (Black) Panthers.”

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Black Panther Party was a controversial political group, and was targeted by then FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, trying to discredit the organization.

Naison was a member of the civil rights organization Congress of Racial Equality as well as the activist group Students for Democratic Society in the 1960s. He hasn’t yet seen Schomburg Center’s “Power in Print” exhibition.

“It was exciting to see people energized, creative … and demanding things instead of waiting for it to come to them,” Naison said of the time period. “I think the art had a lot to do with this.”

Naison credited Emory Douglas — the Black Panther Party’s minister of culture, whose work is featured in “Power in Print” — for creating the images, which inspired people to take action.

“The charisma of those images was extraordinary,” he said. “It was amazing to watch people be transformed before your eyes.”

“As I was walking into the exhibit, I was intrigued with how un-commercial everything felt,” said Lillian Curry, a high school senior, who attended the exhibition with her father and sister.

“The majority of these (posters) have hand-drawn aspects in them.”

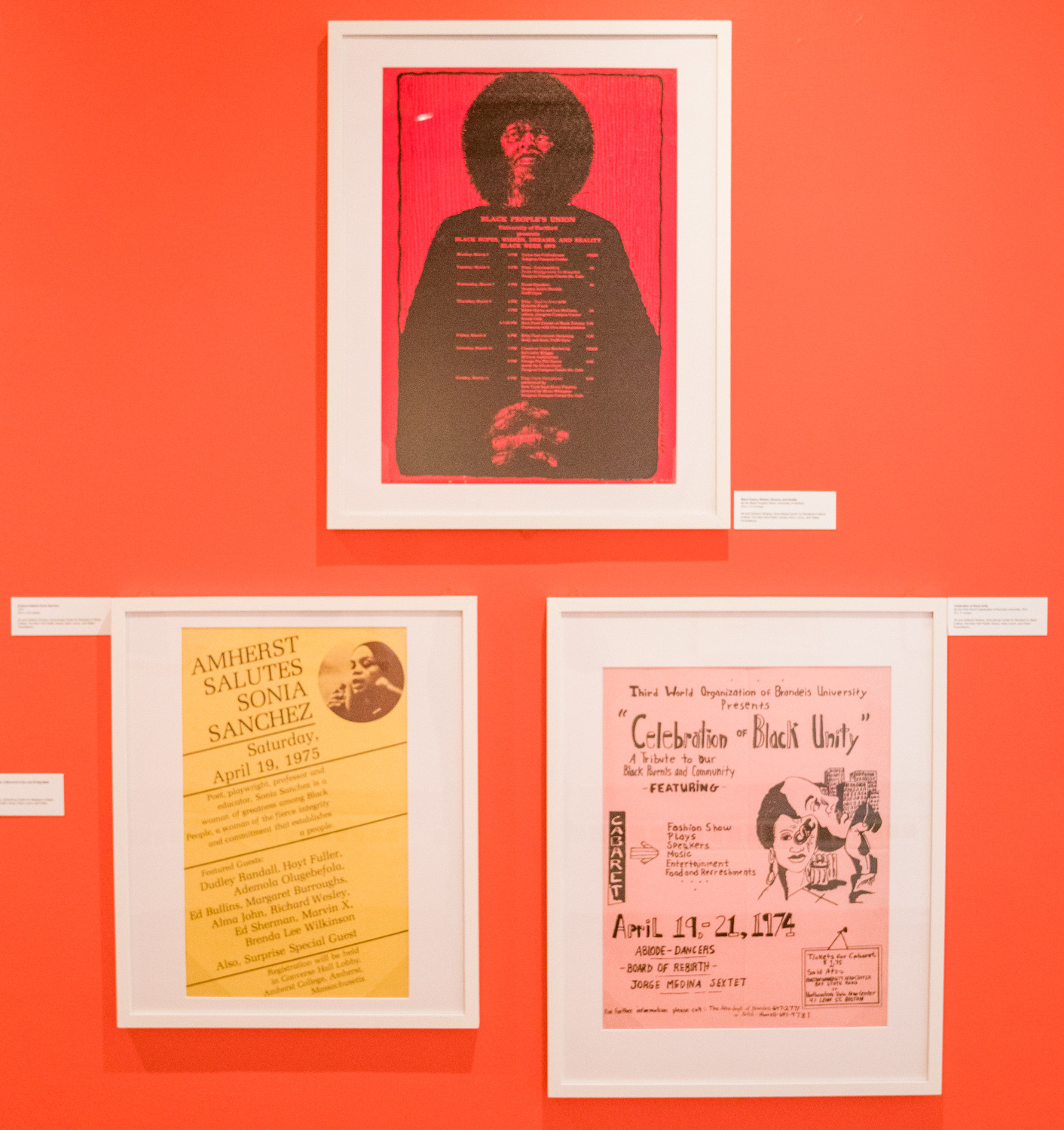

That detail, she added, increased the personal feel and emotional connection in posters like those of Douglas, who she said used the colors pink and black to create the “Solidarity with Oppressed People of the World” piece.

It shows an African-American woman wearing an Afro carrying a gun and spear. He mixed the two hues to create other colors in the poster.

“A lot of the work looked like college kids making the posters,” Curry said. “It was interesting to see that much interest and that much passion coming from all age groups.”

The image of a man yelling with his fist in the air caught the attention of Courtney Wicker.

“I think the chain around the arm symbolized the chain to me of breaking racism,” he said of the 1970 poster “Power to the People” by the Artists Revolutionary Movement.

Although he was born in the late 1970s as the movement was winding down, “the posters just take you back to that time,” Wicker said, adding it made you feel what people were experiencing in the 1960s and 1970s.

Some of the other posters in “Power in Print” urged people to take part in the 1970 U.S. Census with the poster “Make Black Count,” or urging people to vote with “One Man, One Vote,” created by the civil right organization Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

“Posters were the social media and digital design of the 1960s and 1970s — a way to mass-produce messaging through images and text and share information widely,” said Sylviane Diouf, the exhibition’s co-curator.

They were used to “galvanize the masses to support actions to free political prisoners, gain political and social representation, and align with freedom-fighters internationally.”

Others in the nearly 60-piece show focused on activists including Malcolm X and Angela Davis.

“Power in Print” is presented as part of the Schomburg’s Black Power 50 initiative, which explores black power through public programs, youth events and exhibitions, according to its website.

Although the movement lasted a decade, Naison said its impact is still felt today.

“I think this black power movement, black awakening, changed the shape of American universities, changed what we are learning,” he said.

“It changed what people are teaching. It changed what people were studying. It was a revolution in aesthetics, politics and academics, all at once.”