K Grill for sale, kosher rules partly to blame

Dmitriy Berezovskiy had a vision. He wanted to create a high-end restaurant for the Riverdale community “where Jews and non-Jews, religious and non-religious — everyone — could all sit at the same table and eat kosher food together.”

He accomplished that goal in 2015 when he opened the Riverdale K Grill House on the corner of West 259th Street and Riverdale Avenue. But now he wants to sell it and some of the struggles he’s had within the kosher community with it.

As Berezovskiy tells it, K Grill House was a labor of love from the beginning. Making money was never his main objective, as he already ran a successful laundromat and dry cleaning business.

When he first acquired the restaurant space, Berezovskiy said it was “garbage” — the roof leaked, and it lacked electricity and plumbing. So he renovated it, employing his own construction company and spending more than $1 million.

The design, he claims, is all his own creation. “I picked out every piece on the wall and on the floor.”

But to open in that particular location, Berezovskiy was required by his lease to operate as glatt kosher — a special kind of religious food requirement that focuses on lesions in the lungs of prepared meat.

Berezovskiy, however, was fine with that, since Riverdale was “the only Jewish neighborhood in New York that doesn’t have a good (kosher) restaurant to have a nice dinner.”

“You go to Teaneck, there’s a lot of restaurants there,” he said. “You go to Five Towns, Queens, Brooklyn, everywhere, and it’s a lot of kosher restaurants. But here, we have nothing. We have fast-food Mexican. We have a Chinese restaurant — very nice, but it’s small. It’s not fine dining. You cannot do celebrations there.”

Now, barely two years after opening K Grill, Berezovskiy is selling — but he insists it’s not because business is struggling financially.

As he tells it, a slew of restrictions imposed by the local Vaad limiting what he can and cannot sell without losing his kosher certificate makes it difficult for him to compete with other neighborhood eateries. “Vaad” is a Hebrew term that refers to an authorized Jewish representative body, often a council of rabbis, that serves in a supervisory capacity — in this case for the production and sale of kosher food.

For one thing, he can’t use a lot of vegetables and certain meats, he said.

“Broccoli, cauliflower, asparagus, Brussels sprouts, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries — they choked me on this side,” Berezovskiy said. “I cannot serve vegetarian people. I cannot give variety of food. And everybody in the neighborhood — like the Chinese restaurant — they can sell broccoli, cauliflower. And I cannot. I don’t want to break the kosher rules, but it’s very hard.”

The local Vaad also forbids him from buying products from certain well-known, high-quality kosher food companies, he said, such as through Star-K.

But the Vaad isn’t the only group with input. Berezovskiy has been subjected to Kof-K, an internationally renowned kosher certification agency. The restrictions imposed on him by both, he said, are particularly severe.

Neither of the local rabbis Berezovskiy said oversee K Grill House returned multiple requests for comment. Moses Marx of Braun Management, to whom Berezovskiy pays his monthly rent, also couldn’t be reached late Monday.

It’s no secret that running a kosher restaurant is no easy task. But neither is running a restaurant in general. Jay Silver, a chef and restaurateur who recently opened Stone Bridge Pizza in Manhattan’s Midtown East, cited multiple challenges.

“Rents are astronomical in New York City, which makes it very difficult to make a profit,” he said.

Another key factor, he said, is the recent across-the-board minimum wage increase for all restaurant employees from dishwashers to line cooks to workers such as bartenders and servers, who rely primarily on tips to get by.

As a result of paying employees more, Silver said, restaurants must compensate by raising prices.

“And there’s a limit to what the customer will pay for a meal, whether it’s an order of fried eggs and home fries, or a hamburger, or a prime steak,” he said.

But running a kosher restaurant adds a number of additional obstacles, said Elan Kornblum, publisher of Great Kosher Restaurants Magazine.

“The main problem is you’re closed between Friday and Saturday,” he said. “Then you have all the holidays — Passover, the High Holidays, and the fast days. Before you know it, you’re closed 100 days out of the year.”

Add to that the cost of supervision — up to $50,000 that non-kosher restaurants don’t have to pay for, with a mashgiach (literally “supervisor” in Hebrew) and other expenses such as higher food costs — and the prospect of running a kosher restaurant can seem daunting, Kornblum said.

Despite the challenges, he offered optimism.

“It’s survival of the fittest,” Kornblum said. “But at the end of the day, it goes back to service and quality of the food, and there are many success stories.”

For his part, Berezovskiy is ready to move on.

Just after 6 on a recent Monday night, K Grill was quiet, with just one table in the front dining area occupied. Plants hung from wooden beams and circular chandeliers with white cylindrical light fixtures illuminated the place. Lounge music played at a low volume.

The rest of the restaurant appeared to be empty.

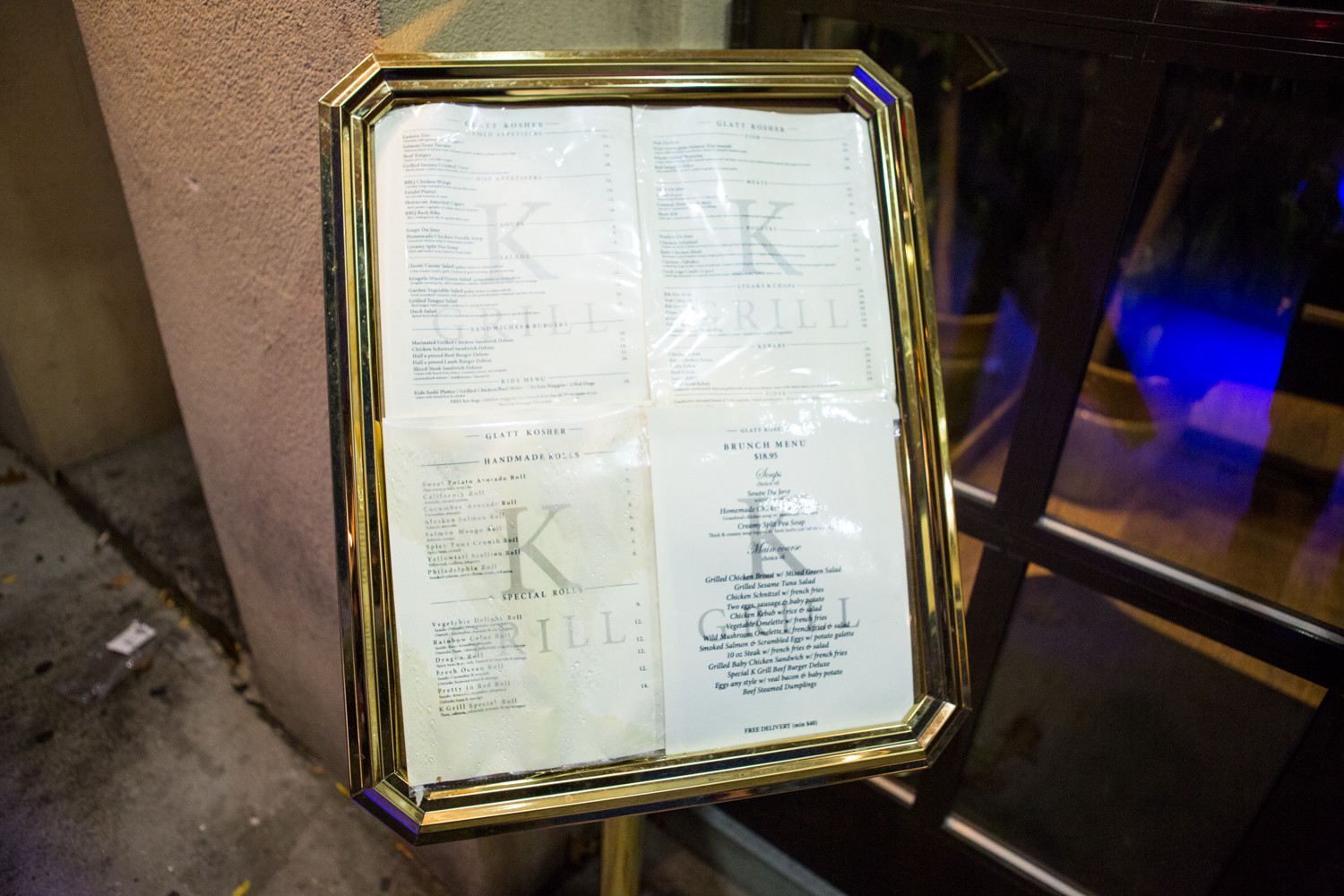

In front, neon lights above the restaurant’s sign cast a soft glow on the pavement below. A sandwich board outside advertised steak, fish, kebabs and salads. A poster in the window urged people to try “the best sushi in town.”

“I’m a religious guy, but I’m not very orthodox,” Berezovskiy said. “I believe in God, I go to synagogue, I do a lot for the community. (But) this is not a synagogue. This is a kosher restaurant, and I have to keep standards.”