To find history, all these students need is a passport

On the left plane of the auditorium, 10-year-olds in bright Native American headdresses, red sailor bandanas and 17th century colonial tricorn hats wriggled in their linked wooden seats.

Kids in bonnets and Puritan hats were on the far right side. And seated between them both was the audience — parents and young siblings, all who had surrendered their morning to watch the children from P.S. 81 Robert Christen School, bring history to life.

“I am a teacher of arts,” said Kim Johnson, who helped lead that morning’s events. “And I use art to teach history.”

Behind the blue curtain, the fourth-graders readied them-selves to teach a lesson that stretched from the Lenape Indians all the way to the Henry Hudson settlement in the form of a show, taking history class to another level.

“I’m very proud of our social studies program,” said Anna Kirrane, P.S. 81’s principal. “We don’t have the kind of kids that when they’re on the news, don’t know the name of their presidents. There’s richness in our learning.”

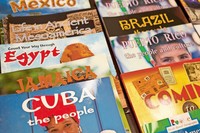

It’s all part of an overall trend in schools to not just study history and the world, but to live in it. That’s what’s happening at Riverdale/Kingsbridge Academy where a curriculum known as “Passport to Social Studies” is in full effect in Barry Steinberger’s eighth-grade honors American history course. Steinberger’s class covers everything between the pre-Columbian and the modern age.

Classrooms across the city are transforming into living history museums. Children are traveling through ancient China like antiquity scholars to author colorful travel guides. And at P.S. 81, they’re serving entire programs on the spiritual history of the Lenape Indians through theatre.

Emily Johnson played a Lenape god during a scene on creation, illustrating this through a call-and-response performance with the other children. The scripts were inspired from the student’s very own writing assignments, discussions and ideas.

Passport is designed for students between kindergarten and eighth grade. Instead of focusing solely upon dates and events, Passport takes it one step further. When learning about a time period, the students are guided by questions that go beyond memorization, challenging them to see the person behind the lesson.

Eamon Martin can explain in detail who his character, William White, really was.

“He was a blacksmith and he came to the new world looking for religious freedom,” the 10-year-old said. “Because in Europe, the king made everyone practice the same way.”

Cian Gaughan played the captain of the Mayflower. As the children waved back and forth to simulate waves, Gaughan explained the struggles settlers encountered while traveling to the new world. Children fell to the floor to show death from fever, and one girl held a baby doll while she complained about the difficulties of being a mother at sea.

As captain, Gaughan even had to save a fellow settler that had flipped overboard, which was the 10-year-old’s favorite part.

“You’re nervous, but I really like it when (his family) come because it makes you feel really good when they’re there,” Gaughan said. “You feel the support.”

Within the Passport program, students also are given the opportunity to use digital resources from cultural institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the New York History Society and the Museum of the City of New York. This allows students to have more of a complete education of state history, according to the education department, that isn’t typically covered in regular studies.

The city’s education department introduced the Passport program in 2016. Since then, it’s been adopted at schools around the city, now reaching 70 percent of them.

P.S. 81 students also use technology like Google Classroom to talk about what they are learning. Google Classroom is an online tool students and teachers use that place assignments and other class work online, making it accessible through a computer or tablet.

It creates a more paperless — and instant — working environment for classrooms.

It also added new dimensions to the class’s study on colonialism, representing what they have learned artistically through their Mayflower production.

“They may not know what pi is equal to, or they may not remember how to simplify fractions, but they certainly will remember Henry’s sweet settlement and their experience,” Kirrane joked.