20 + 10 = classroom crush, says Diaz

New York City’s schools teach 1.1 million students every day on more than 1,700 campuses. And it’s probably no surprise that many of them are overcrowded.

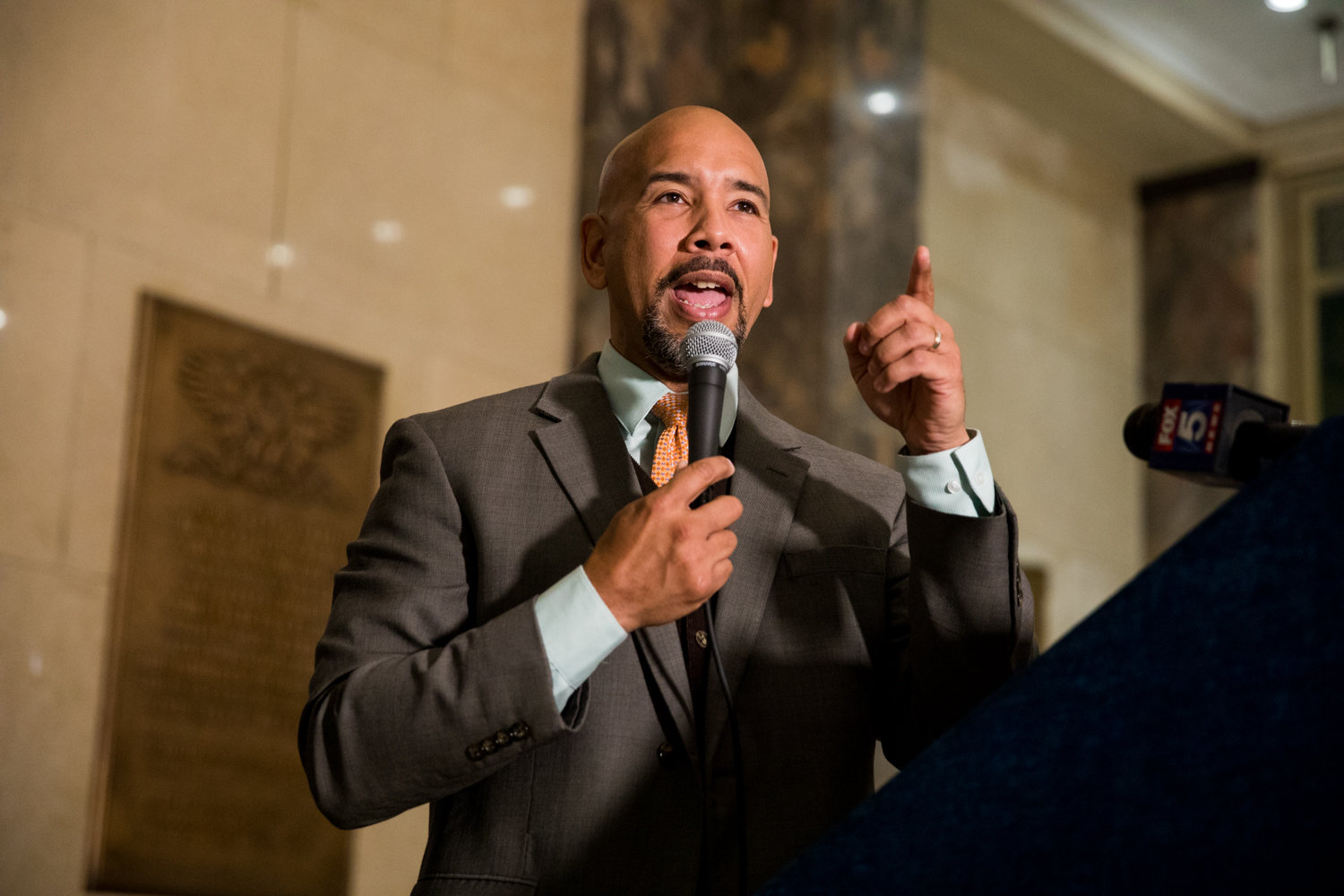

That hasn’t stopped Bronx borough president Ruben Diaz Jr., from looking closely at the issue. And now he’s calling on the School Construction Authority — which is responsible for building and maintaining schools — to make drastic changes to its approach in alleviating school crowding.

Diaz found that 38 percent of the city’s public schools are operating over capacity, meaning more than 95,000 students are enrolled in 675 schools his study has deemed overcrowded.

“For my entire political career, I’ve been moving through schools, talking to people in New York City,” Diaz said. “There’s a lot of districts that are overcrowded or on the border line.”

With ever-increasing housing development, and the school-aged population of the Bronx expected to rise over the next decade, Diaz outlines 10 recommendations for SCA reforms, including adopting a new process for identifying new school sites, leasing additional school space in overcrowded districts, and better studying the effects on local schools created by new housing development.

That last recommendation is especially important to Diaz. Because students are divvied up based on where they live, overbuilding new housing in a school zone can push local schools over capacity.

In the Bronx, for example, 45,000 new housing units have been developed over the last decade, Diaz said. Yet school construction and expansion has not kept pace. Most — if not all — large-scale housing projects are subject to citywide review through the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, but impact to schools are rarely, if ever, analyzed as part of that process.

“They have to take a broader look at the neighborhood than just that site,” Diaz said. “How many new police officers will be needed? How much transportation infrastructure? How much sanitation?”

A closer look

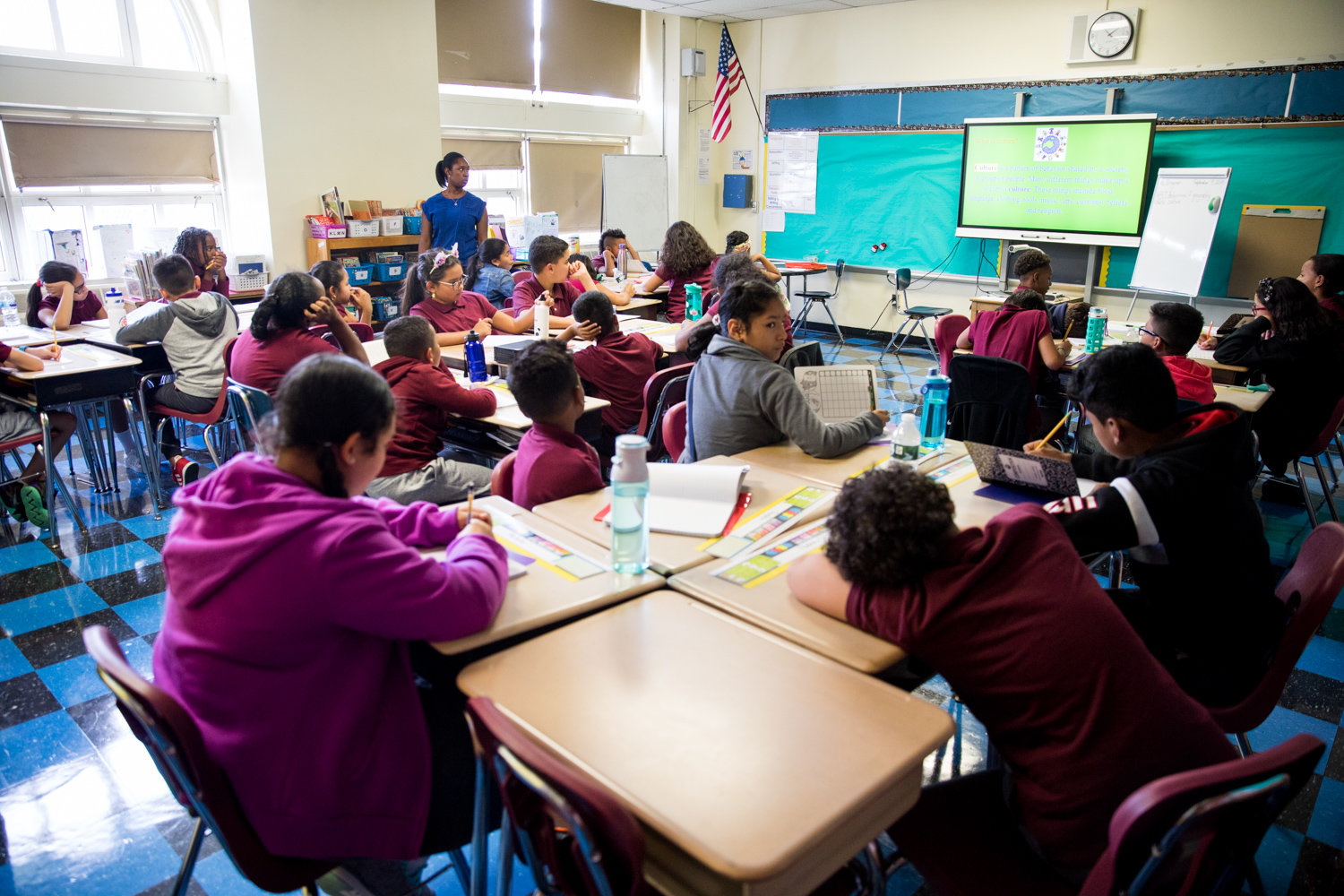

P.S. 7 Milton Fein School in Kingsbridge has operated over capacity for at least a dozen years, said principal Miosotis Ramos. Over a period between 2015 and this year, P.S. 7 was as high as 141 percent capacity. The school operates best with 560 students, officials say, but actual enrollment over that time ranged around 700 or more.

Beginning this fall, however, P.S. 7’s student population dropped 17 percent to 640. The reason? Some 100 students didn’t “graduate” from nearby P.S. 207’s second grade into P.S. 7’s third grade. P.S. 207, located just a few blocks away at Godwin Terrace, expanded a bit, allowing second-graders there to stay for third grade.

That was a welcome respite for Ramos and her P.S. 7 faculty.

“It really created an issue of very large third grade classes, and many third grade classes,” Ramos said. “Right now, we have three third grade classes, which we’ve never had. The norm was seven classes.”

With an average of 32 students in each class, that would put 224 students in a single grade at P.S. 7 — nearly half of what officials would consider capacity for the elementary school. That put pressure on teachers and administrators to keep an overcrowded school running smoothly while still trying to provide a quality education.

“It makes it difficult for teachers to organize their room in a way that’s free for students to move around, to have centers and areas for students to spread out,” Ramos said.

But schools like P.S. 7 aren’t just limited to who lives nearby, Ramos said. Schools can pick up more students from outside their zone.

“One of the issues is that parents have choice at the end of the day,” the principal said. “If they go to enrollment and push it and say, ‘This is where I want to be,’ they usually find them a seat.”

It’s difficult enough to save seats for children living in the neighborhood, Ramos said. Having better zoning enforcement could allow her administration to better manage enrollment.

Inaccurate data

Projections could help Ramos and other principals plan for the coming academic year better, except they’re often wrong. That affects not just how many seats are available, the principal said, but funding as well.

“Since I’ve been the principal, I’ve always had an issue with the projections,” Ramos said. “Usually we get money taken away because we didn’t meet the projection.”

For example, P.S. 7 was projected to have 690 students enrolled, but instead welcomed just 640 when school started earlier this month.

“That may mean a significant amount of money,” Ramos said.

Even though P.S. 7 is below the city education department’s projection, the school still operates above capacity, Ramos said. That additional funding is needed for after-school projects and maintaining her staff.

“If I had hired more this year, then next year — when the fifth grade gets smaller — I’ll have excess,” Ramos said. Having too many teachers and other support staff would likely mean layoffs, and job instability.

Diaz called the school department’s enrollment projections “antiquated,” but admitted wrong numbers weren’t entirely the School Construction Authority’s fault. The agency struggles to maintain contact with other agencies involved in neighborhood development, which would help feed more accurate data into the projections.

The construction authority does maintain a five-year capital plan designed to accommodate the growing student body. Yet, past plans failed to create the number of seats needed, Diaz said. For example, the 2010-14 capital plan funded just 68 percent of the seats needed for kindergarten through eighth grade.

Even worse, the borough president added, many capital projects often run over budget without actually accomplishing their goals.

Much bigger classes

Cheniese Grayman, joined P.S. 7 as a fifth-grade teacher after spending time in a Bronx charter school. At that school, Grayman’s classes averaged about 20 students. Here, it’s 30.

“For me, it’s hard to manage the different personalities you get with such a large crowd of students,” Grayman said. “With 20, it’s a little easier to manage, to understand where they’re coming from, to get to know everyone.”

With so many students, P.S. 7 lacked a dedicated science room in previous years, as well as music or dance rooms, Miosotis said. Dance was taught in a vestibule at the school’s entrance, while P.S. 7’s newly hired science teacher had to carry her equipment across the school to various classrooms.

Now that the student population has dropped, there are plans to renovate a room exclusively for dance — with mirrors and a bar — while the science teacher has finally set up a more permanent classroom.

But P.S. 7 isn’t alone when it comes to overcrowded schools in the neighborhood. P.S. 24 Spuyten Duyvil was 23 percent over capacity as of January 2019, while P.S. 81 Robert J. Christen School was 30 percent over.

While they shouldn’t have to do it, each of the schools, Miosotis said, have found a way to adapt.

“I want to keep my kids,” the principal said. “If they’re here, they’re here for a reason. Having 640 students is like we’re having a party, this is great. I’m not complaining about it.

“We can manage. We have really good systems in place.”