Author returns home, fighting for immigrants

Cities are the keepers of all kinds of people. A neighborhood can be a community of shared history and culture, a home within a home. For some, it is a home away from home as well.

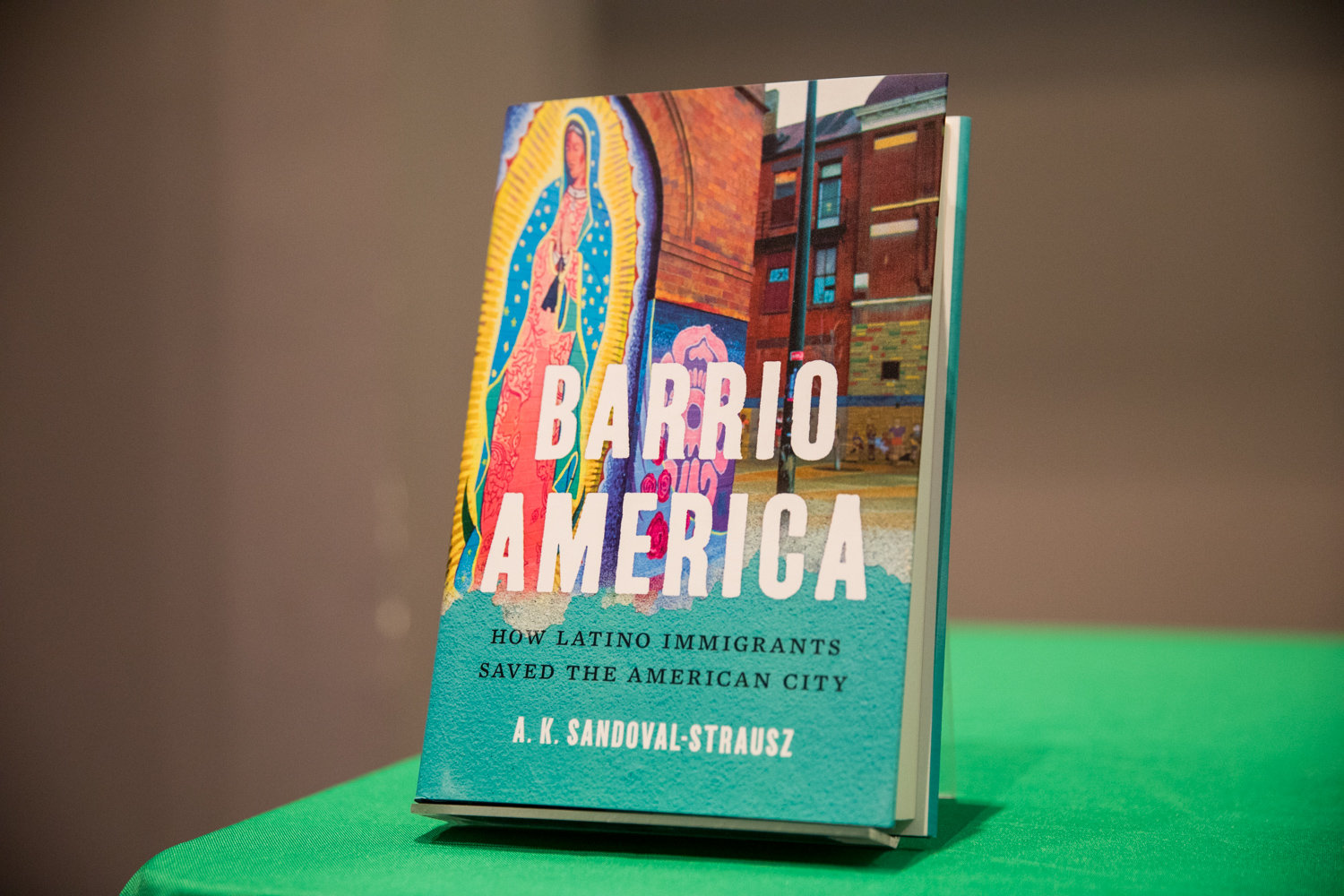

That’s just one of the claims made by Andrew Sandoval-Strausz, a professor of Latino studies at Pennsylvania State University, in his new book, “Barrio America: How Latino Immigrants Saved the American City.” Sandoval-Strausz brought those ideas to Manhattan College in February, in a lecture based on his book, returning to the borough he grew up in.

“I was born here, and lived here until I was around 4,” Sandoval-Strausz said. “Once, my friend and I went to see a film called ‘Fort Apache, the Bronx,’ featuring Paul Newman and other cops who thought they couldn’t leave their cars or they’d die. Lots of violence and murder. Oddly enough, when I left the cinema with my friend that day, the Bronx didn’t look like that.”

According to Sandoval-Strausz, that 1981 film from Twentieth Century Fox was just one in a long line of anti-city movies, a series of films that dominated theaters in the 1970s and 1980s, depicting urban areas as dangerous and filled only with crime and the undesirables of the world. More often than not, Sandoval-Strausz posits, those undesirables were depicted as African-Americans and Latinos.

“Films made us have ideas like that,” Sandoval-Strausz said. “People thought the age of the major city had died, but by the 2000s, they had to recognize that they were wrong. They had to recognize that immigrants are necessary to accommodate a deteriorating area, and bring it back to life.

“In Dallas and Chicago, the areas with the highest population growth are the Hispanic communities.”

Sandoval-Strausz’s parents divorced when he was young, so his time was split between his mother’s home in New Rochelle and his father’s home in Manhattan. He moved back to Manhattan in his college years, then to Chicago for graduate school.

After living in enormous cities, Sandoval-Strausz had seen and researched the opposition immigrant communities face in this country, and has found himself agreeing that one contemporary factor has been a sort of plague in urban areas: those who are more affluent, pushing the not-so-wealthy out of a neighborhood.

“The gentrification story has become very, very intense,” Sandoval-Strausz said. “Particularly in Puerto Rican and Latino neighborhoods. I keep referring back to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s ‘In the Heights’ because the whole backdrop of that is gentrification. Latino neighborhoods are caught between people that really hate them — like immigration authorities — and people who love them too much and destroy them by moving in and inadvertently kicking them out.”

Sandoval-Strausz admits that his memories of the Bronx are nothing like the borough’s present day. A CNBC report from 2018 even highlighted how some real estate developers had begun referring to the South Bronx as “SoBro” in an attempt to mimic the chic neighborhoods of Manhattan, a turn of events that seemed laughable 30 years ago.

“Cities are strange places,” Sandoval-Strausz said. “A neighborhood like Dumbo in Brooklyn was just a place where people worked, but now it’s a place where yuppies live. Yuppies also want to live in South Bronx now because it’s so close to Manhattan. You get these young professionals that either want a cache of area, that has a great view, or a cache of proximity and culture, like South Bronx.”

Sandoval-Strausz didn’t just focus on gentrification. Efraim Tello, a sophomore at Manhattan College, was particularly struck by Sandoval-Strausz’s statements on how a neighborhood’s population was divided in previous decades, and how that could still be seen today.

“I’m Mexican, and I wanted to see how he’s showing immigration in America,” Tello said. “A lot of what he said made sense — how there are buffers between black, Mexican and white populations in different parts of cities, or even towns like back in Arkansas where I live — and also how Mexican and black populations are mistreated.”

Sandoval-Strausz maintains that areas like Tello’s central Arkansas home are dying due to a combination of job scarcity and population decline, and that more immigrants could revitalize those kinds of places.

“As of 2000, more immigrants move directly to suburbs than they do to cities in the United States,” Sandoval-Strausz said. “Fewer of them are going to rural areas. But in terms of population growth in rural areas, Latino population growth is much faster in non-metropolitan counties.”

Although Sandoval-Strausz and several other theorists, academics and activists have presented carefully detailed statistics and facts regarding the supportive nature of immigration, the professor finds that not enough has changed when it comes to overall optics.

“Think about a Rust Belt factory town,” Sandoval-Strausz said. “That area needs new people. But immigrants have famously been mistreated in public and in school. I really wonder if in the age of the Trump presidency people will think that a smaller community is just too unfriendly, and that community will die.

“What’s funny about yuppies in cities is that, at the very least, they reliably don’t vote for Trump. That’s the best that can be said. That can’t be said for small towns, however.”

In Sandoval-Strausz’s eyes, the necessity of welcoming an immigrant community with open arms is the only way a revitalized city population can spread out and save the rest of the country as well.

“America’s birth rate has slowed pretty dramatically,” Sandoval-Strausz said. “Slowed to 30-year lows. It’s far too slow to maintain our economy and our institutions — be it in the work force, Social Security, military — there aren’t enough Americans. Immigrants are the only ones keeping us out of a demographic downward spiral.

“We must return to our greatest tradition of welcoming immigrants.”