Can’t pick just one candidate? Now you don’t have to

Ranked-choice voting is meant to even the playing field for those running

The special election to replace Andrew Cohen on the city council is less than two weeks away.

Along with having to campaign during a pandemic, the six candidates in the March 23 race also have to contend with a new way to cast a ballot: ranked-choice voting. This special election, along with another one held the same day for the seat once occupied by new U.S. Rep. Ritchie Torres, will only be the third test case of this new voting system in the city following two races in Queens last month.

While the candidates might understand ranked-choice voting inside and out, many voters may still wonder how all of it works.

Fortunately, the answer to this question is a lot less complicated than it may seem. At least the voting part — which is the only part anyone casting a ballot will need to know when they visit the polls beginning with early voting next week.

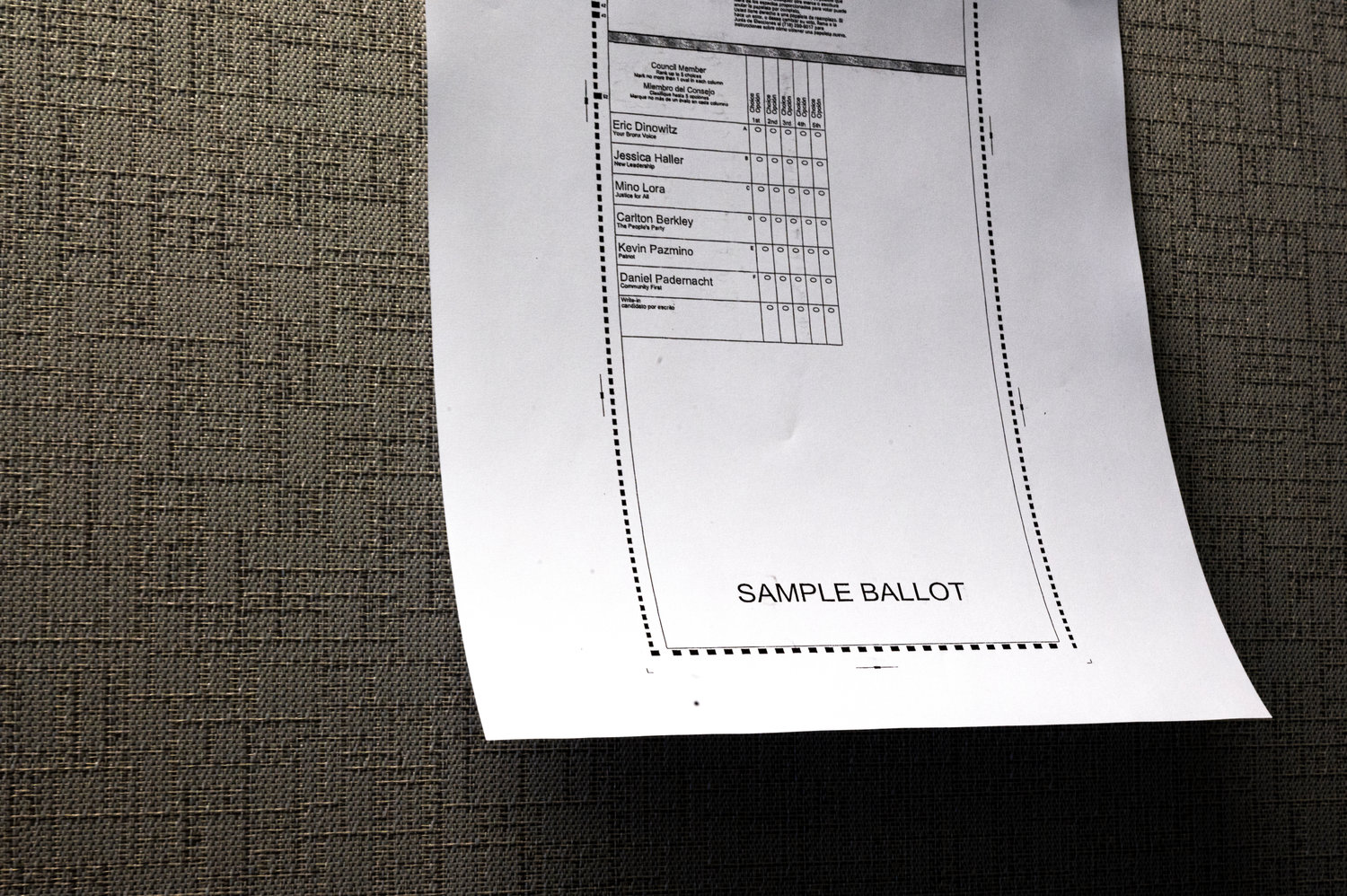

The ballot lists the candidates on the left side with a ranking index at top.

Voters then rank their choices one through five — with one being their top choice, and five their lowest. They still have the option to pick less than five or choose only one if they want.

They also can write in candidates.

However, the best way to get the most out of this new system is by ranking as many candidates as possible.

“The more rankings they put on their ballot, the longer their ballot continues to work for them,” said Sean Dugar, education campaign program director at Rank the Vote. “And the more voice they have in the electoral process.”

After getting their “I voted” sticker from a poll worker, the voters’ role in this process is complete. But for candidates and the city’s elections board, the “fun” is just beginning.

Counters will provide an initial tally that night. If one of the candidates receive 50 percent of first choice votes in the first round, they’re the winner, and the counting — outside of absentee and overseas ballots — is over. If nobody gets a majority in that initial round, the lowest vote getter is eliminated. Their votes are redistributed to whomever the voters chose as their second-place candidate.

The process of eliminating the lowest-scoring candidate then continues — distributing their next highest ranked votes — until only two candidates remain.

Going into these additional rounds would likely mean a winner wouldn’t be named in the Cohen special election race until mid-April at the earliest.

Still, proponents of ranked-choice voting argue the system allows a broader swath of voters has an ultimate say in who should represent them in local office.

Ranked-choice is designed for races like specials, where there’s typically multiple candidates who, in the past, would’ve simply been selected on who had the most votes — even if that tally was far below 50 percent of the total

This was a process known as “vote splitting,” meaning while the person with 30 percent, for example, may have gotten the highest number of votes, most people voted for other candidates — the votes were just split up amongst the others.

Ranked-choice voting will eliminate that problem, said Kathy Solomon, who serves on Northwest Bronx Indivisible’s steering committee.

“You’re going to have more agreement on the person who is finally elected than you would otherwise have (had) in a race with more than two candidates,” Solomon said. “The elected official will truly represent more people than they formerly did.”

Another benefit, Solomon said, is that it forces candidates to appeal to the broadest group of voters possible. This means candidates might make an effort to reach voters who were often overlooked under the old system.

Additionally, it also could lead to less negative campaigning, she added, because candidates don’t want to alienate first-choice supporters of other candidates who could rank them lower on the ballot.

But there’s been some concern voiced by critics who think candidates might take less-hard stands on hot-button issues in an attempt to appeal to as many people as possible. Some also are concerned there isn’t enough of an effort to educate voters on the new system, which could lead to confusion and mistakes at the ballot box.

Ranked-choice also eliminates the need for runoff elections, Dugar said, which are usually very low turnout and tend not to reflect the diversity of the city overall. Not to mention very expensive.

Additionally, it promotes candidates from marginalized groups — like people of color, women and those from the LGBTQ community, Dugar said. It gives them a chance to have a greater voice in the race, eliminating vote splitting, usually cited as a reason why candidates are sometimes convinced to “wait their turn.”

The system is new, yet campaigns already are developing strategies to get the most out of ranked-choice voting, Dugar said.

The frontrunner strategy is one where the perceived leading candidate asks voters to rank them somewhere on the ballot if they aren’t the voter’s first choice. For instance, the special election perceived frontrunner Eric Dinowitz is campaigning to be voters’ first or second choice, according to spokeswoman Daniele de Groot.

The underdog strategy is different because it involves contenders forming alliances with one another. Candidates who share some commonality will pair up, Dugar said, and ask voters to rank them first and second on the ballot.

These commonalities could range from policy positions to identity.

“Often, folks will either vote for the candidates that are the same ethnicity as them, or will vote for women candidates, or LGBT candidates together,” Dugar said. “So, it makes sense that two women will partner together and say, ‘Hey, let’s elect a woman to the seat. Yes, our issues may be different, but identity matters.’”

Arts non-profit executive Mino Lora and environmentalist Jessica Haller are the only candidates in the local race using this strategy. The two obviously overlap on identity as the only women in the special election race, and both have similarly progressive platforms — although Lora is considered by some to be further to the left than Haller.

The other four candidates — Dinowitz, filmmaker Kevin Pazmino, real estate attorney Dan Padernacht and retired New York Police Department detective Carlton Berkley — are all going in it alone.

No matter what strategy candidates are using, Dugar said his biggest piece of advice is for them to educate voters on ranked-choice voting.

“We find that the first candidate to explain ranked-choice voting to a voter becomes their first choice,” Dugar said. “Voters look to candidates and how they campaign as how they’ll also act as an elected official.”