Conflict through a humanist lens

There’s something to be said for a photograph that can linger in your mind. It can be like a lost treasure or an apology — something lost, or found, or neither.

Learning of the photographer, however, is a discovery in and of itself.

For 10 years, the RiverSpring Health’s Hebrew Home at Riverdale has curated the Derfner Judaica Museum, named after benefactors Harold and Helen Derfner. It maintains an ethos of exploring elements and themes of Jewish art and culture.

“Our Judaica, which is Jewish ceremonial art, stays in place,” said Susan Chevlowe, the museum’s chief curator and director of the museum. “But we do change exhibitions in this space.”

The most recent change features the photographs of Leonard Freed, a first-generation Jewish Brooklynite, journalist, author, and previous member of photojournalist co-operative Magnum Photos.

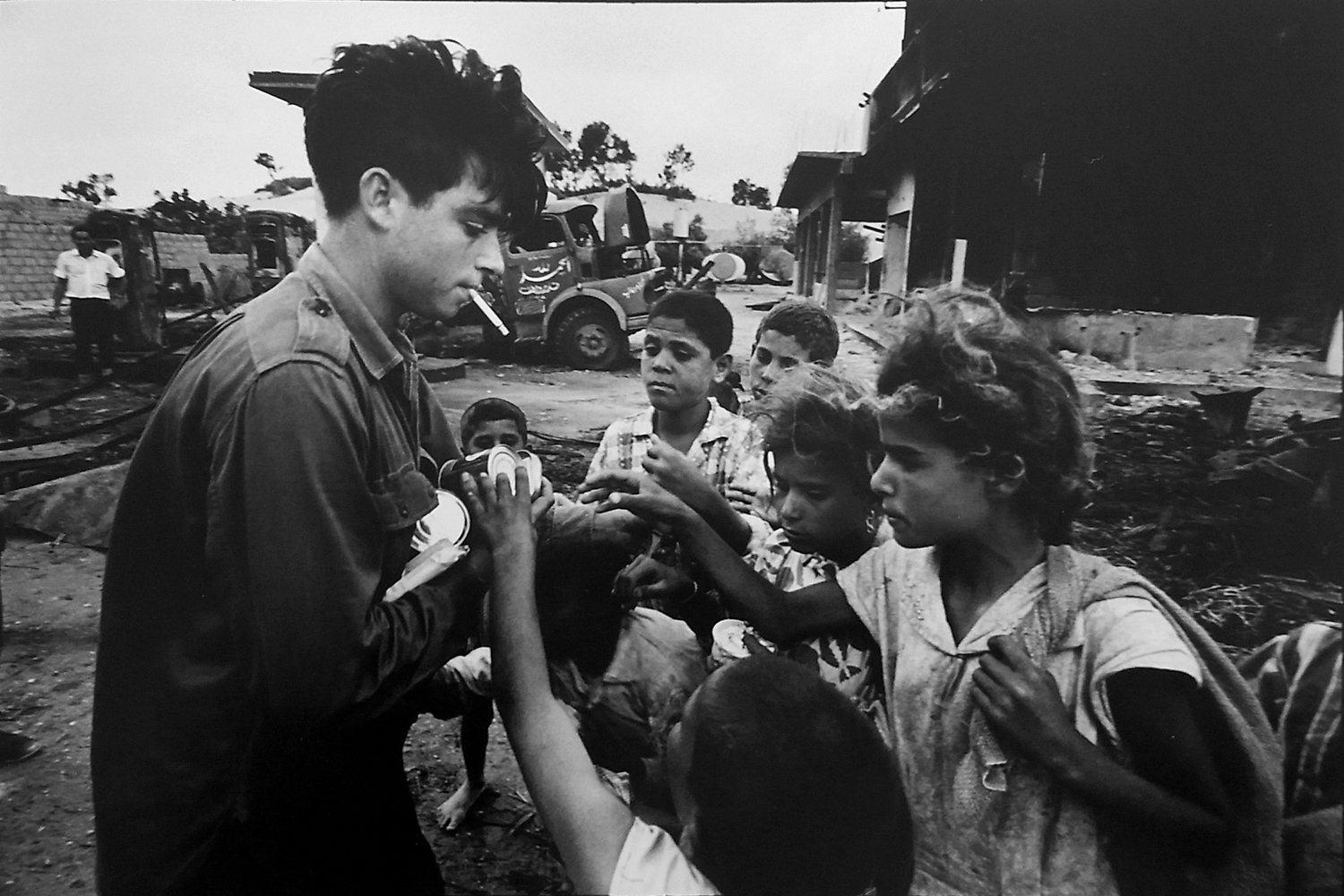

The show focuses on Israel Magazine, an American-Israeli publication Freed supplied images for between 1967 and 1968. Freed was a staff photographer there for the 15 months he was in Israel, documenting the aftermath of the Six-Day War. The magazine’s aim was to be a “bridge between Israel and the Diaspora.”

Freed was a part of a generation of photographers that held a humanist angle, according to Chevlowe — those who documented reality with a heart.

Freed was close to Cornell Capa, brother of Spanish civil war photographer Robert Capa, who organized a variety of exhibitions during his time. Chief among them was the “Concerned Photographer” show at the Riverside Museum in 1967, the Upper West Side space that’s now home to the Nicholas Roerich Museum. There, the work of Freed, Cornell and Robert Capa, David Seymour and Dan Weiner detailed conflicts from around the world, ranging from individual difficulties to societal struggles.

“These artists and participants are attracted to conflagrations like war, but their purpose is very humanistic,” Chevlowe said.

Freed’s coverage of the Six-Day War is “an indices of violence,” the curator added, rather than a presentation of destruction. One photo depicts the remains of a soldier on a desert beach in Sinai. In the distance, a man — standing in trunks — is preparing to swim in the water.

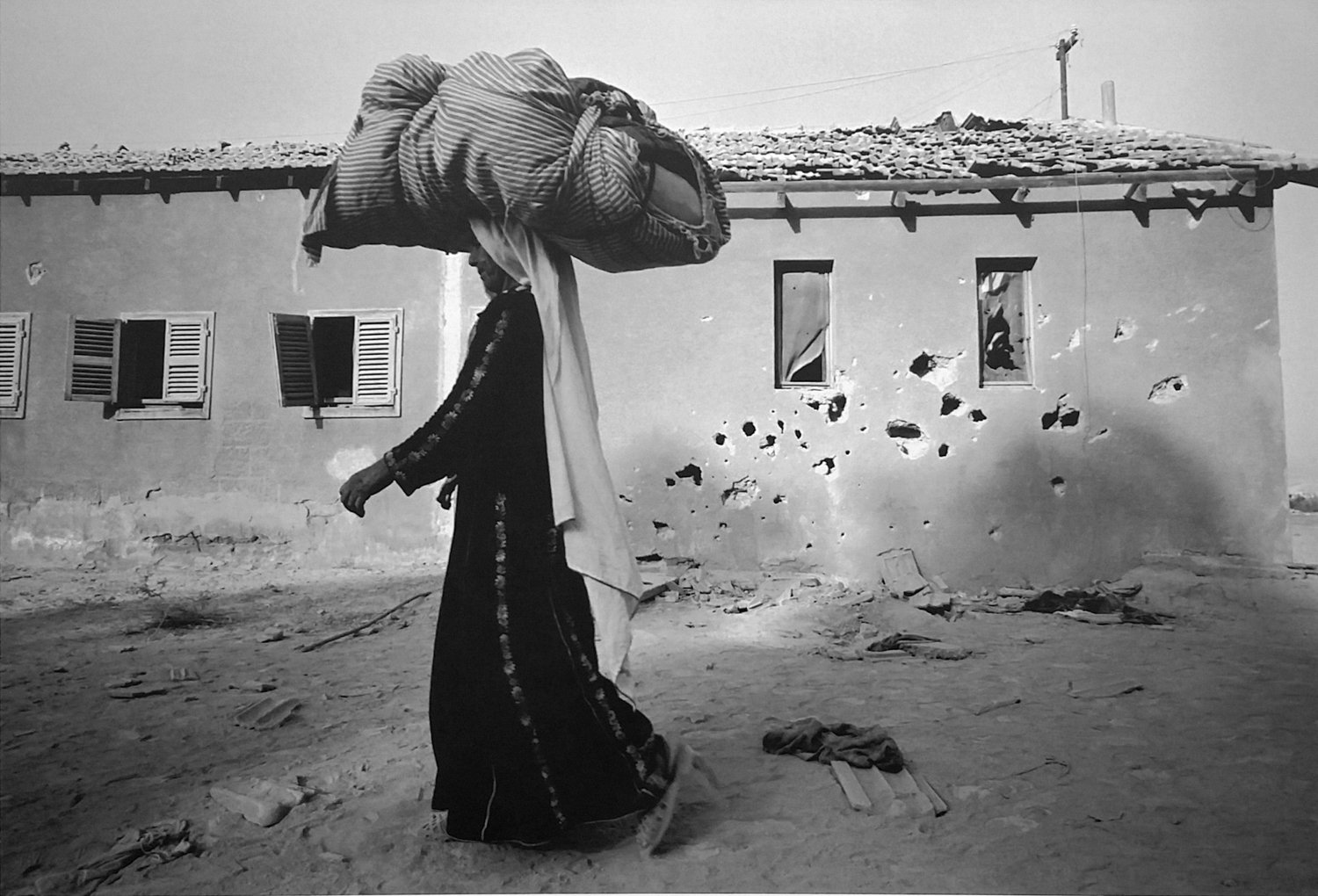

Another image depicts an Arab refugee woman on her way toward Allenby Bridge that crosses the Jordan River near Jericho. She is carrying her possessions on her head, and she’s alone.

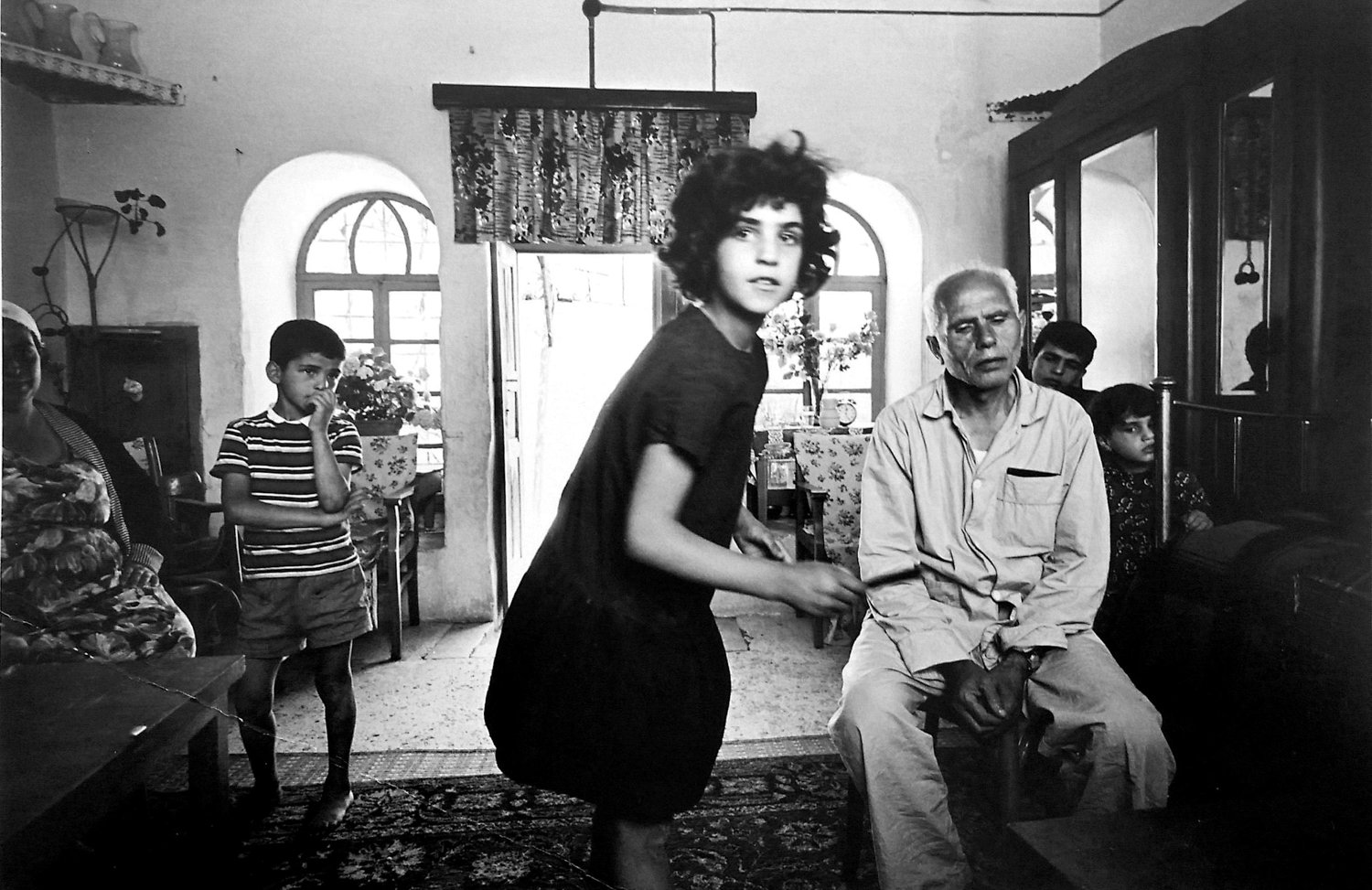

Freed’s eye for the human regardless of creed focused his gaze on refugees, Palestinians, and other minority groups within Israel, within the area of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, and also in the new lands. A class for the blind in occupied Ramallah, or a Druze home in the Golan Heights, as well as the lone woman walking to Jordan.

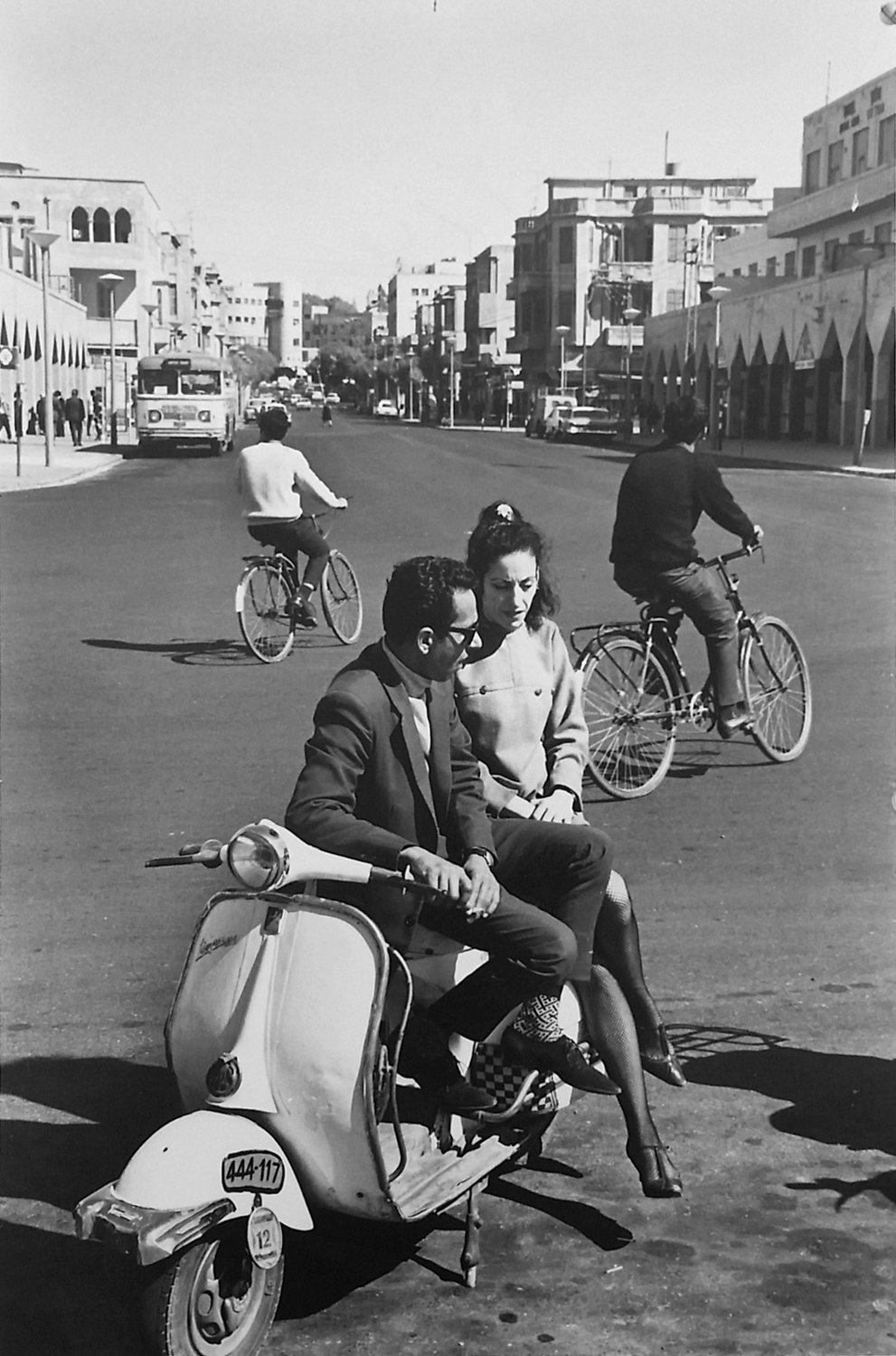

But there was more in Freed’s vision, Chevlowe said. Something that lived in tandem with struggle. “There’s a dialogue happening in the exhibition.”

A conversation between children, and men and women of all sects. There are disapproving mothers, a religious couple walking down a hill, women at a fresh-water spring near the Dead Sea.

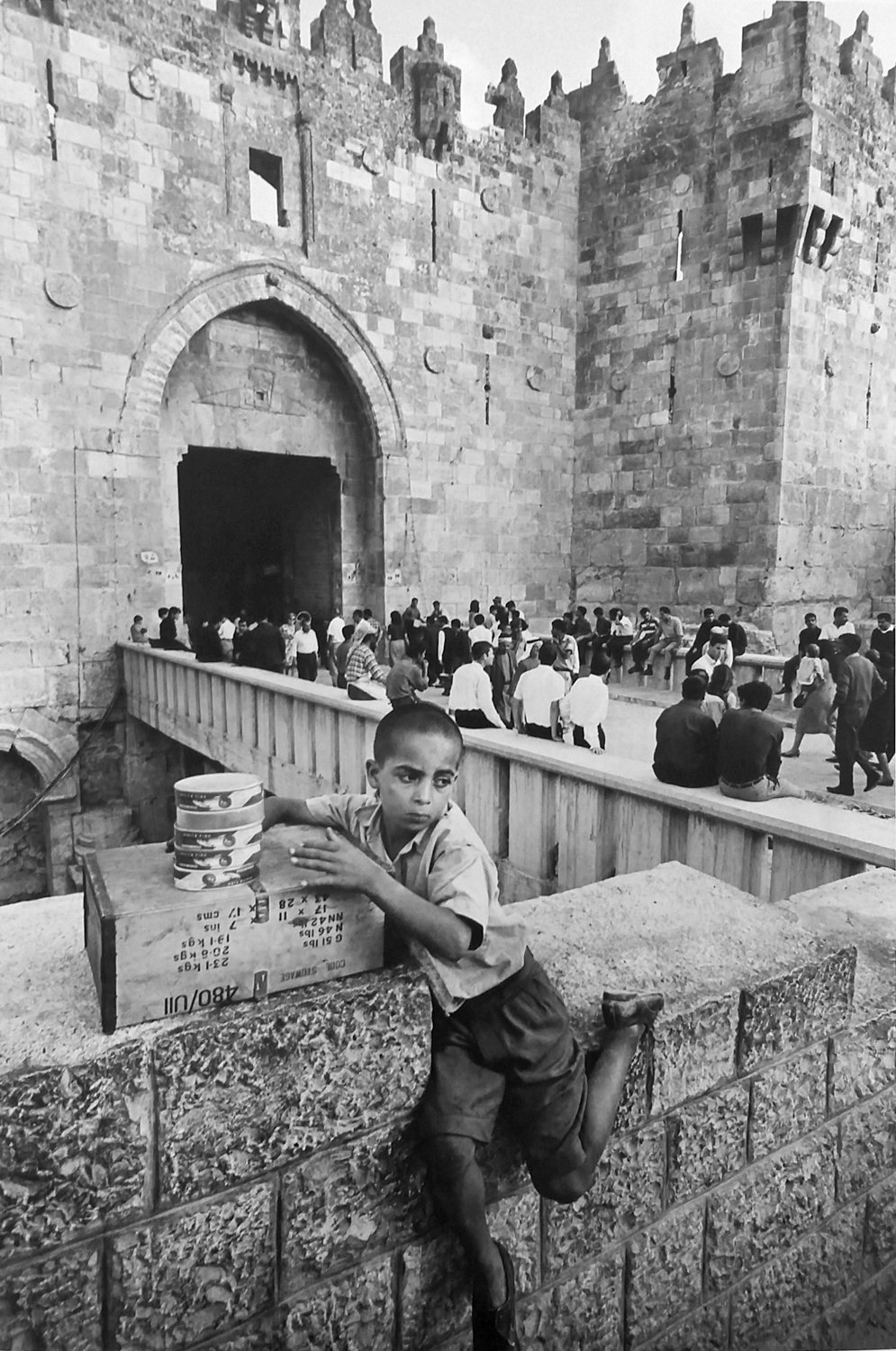

Freed photographed a young Arab boy sitting by the entrance to the Old City’s Damascus Gate. A caption attached to it reads, “At the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem, an Arab child peddles Chinese wares.” The boy is selling canned fish. The writing on his box is not Chinese. The caption is not by Freed.

That’s because the photographer was not in control of what was written to accompany his photographs for various publications. A stranger many miles away would ultimately frame the context of Freed’s work.

“That’s why his 1984 book ‘Dance of the Faithful’ is so important,” Chevlowe said. “He reproduced some of the same photos, and we can see what they meant to him.”

Freed’s book, a collection of photos concerning Judaism and his relation to it, contained a caption for each photograph, Chevlowe noted. He saw the photographs he’d taken years before and found something of himself within them, describing the captions as “a reference to an emotional experience which I was unable to capture as a photographer.”

“Dance of the Faithful,” however, was only published in French.

Freed died in 2006, following a long career documenting conflict and life around the world, including the American civil rights movement, the Romanian revolution, and the New York Police Department. Yet scholarship of his work is scarce.

Freed’s widow, Brigitte, was always by his side as his printer and partner, and as vital to the art and job of photography as Leonard himself. Brigitte has promoted galleries, symposiums and exhibits of her late husband’s work, including the current one at the Hebrew Home at Riverdale, the contents of which were lent to the museum from Leonard Freed’s archives. Thanks to Brigitte Freed, visitors to the Derfner Judaica museum won’t lose the teachings and insights offered by Freed’s work. Because it is important.

“Anything we do today going forward has to be done with a consciousness about how we got here,” Chevlowe said. “What the photography does is connect us exactly to the humanist side of it — the person-to-person side of it.”