Portraits of Resilience

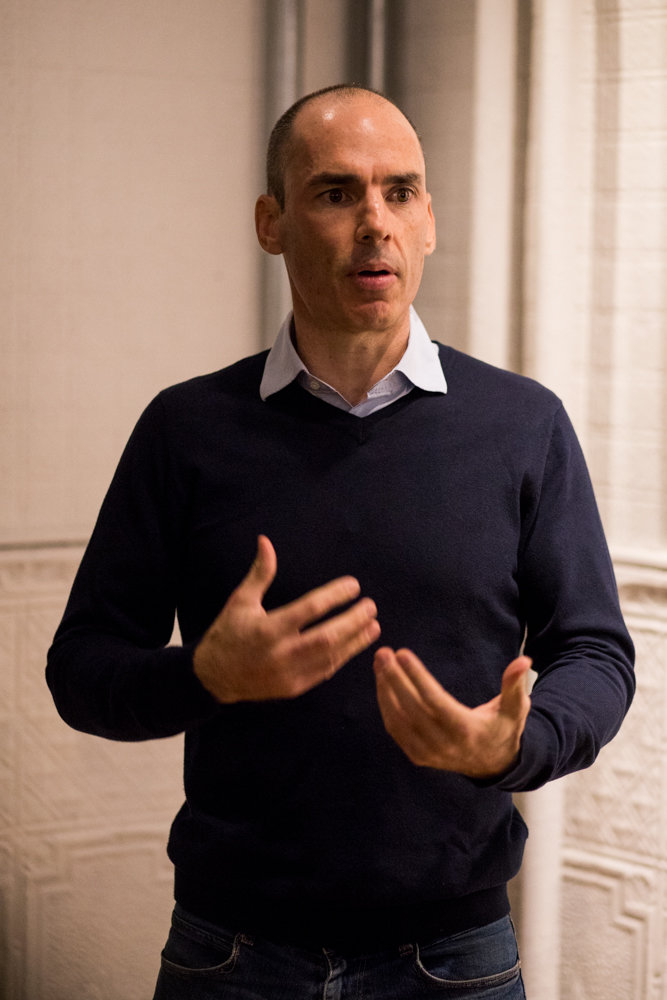

Robin Hammond found himself at a crossroads in 2014.

The photographer was working on assignment in Lagos, Nigeria, when he heard about five young men arrested for “committing gay acts” in northern Nigeria. Hammond wanted a better understanding of what they were going through, so he sought them out.

“When I heard their stories,” he said, “it was incredibly moving.”

By the time Hammond met with them, their 14-year sentence had been overturned, but it was a bittersweet victory.

“They were completely ostracized by their family members,” Hammond said. “Their physical scars will heal, but that rejection from the people who should love them the most, I think, is what hurt them the most.”

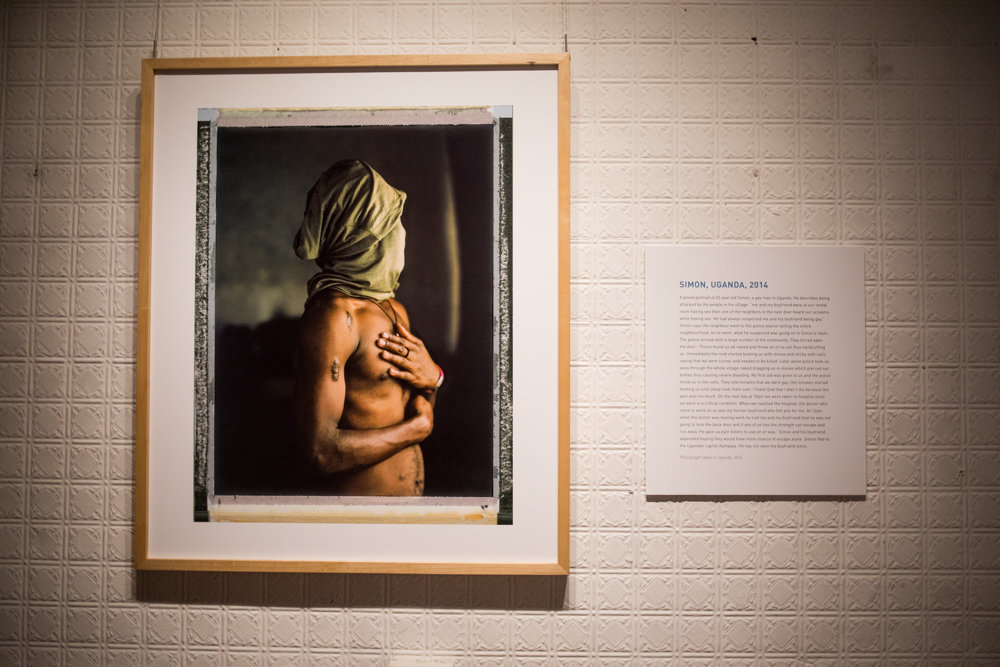

As a photographer, Hammond wanted to communicate their story visually, but he understood their concerns for their safety. Hammond had with him a large-format Polaroid camera — the kind that prints pictures on the spot — and worked with the men to figure out a way to photograph them where they’d feel comfortable.

“If you’re not happy with it, you can destroy it,” Hammond recalls telling them.

It was in that moment that his ongoing documentary portrait series, “Where Love is Illegal,” came into being. An exhibition of the work is on display at the Bronx Documentary Center through March 24, and it comes 50 years after the Stonewall Riots that marked what many consider the official start of the gay rights movement.

The series is an aesthetic departure for Hammond who has photographed humanitarian issues all over the world. Many of his photographs are in the classic photojournalistic tradition. He bears witness to the world, and viewers — by extension — are transported into it.

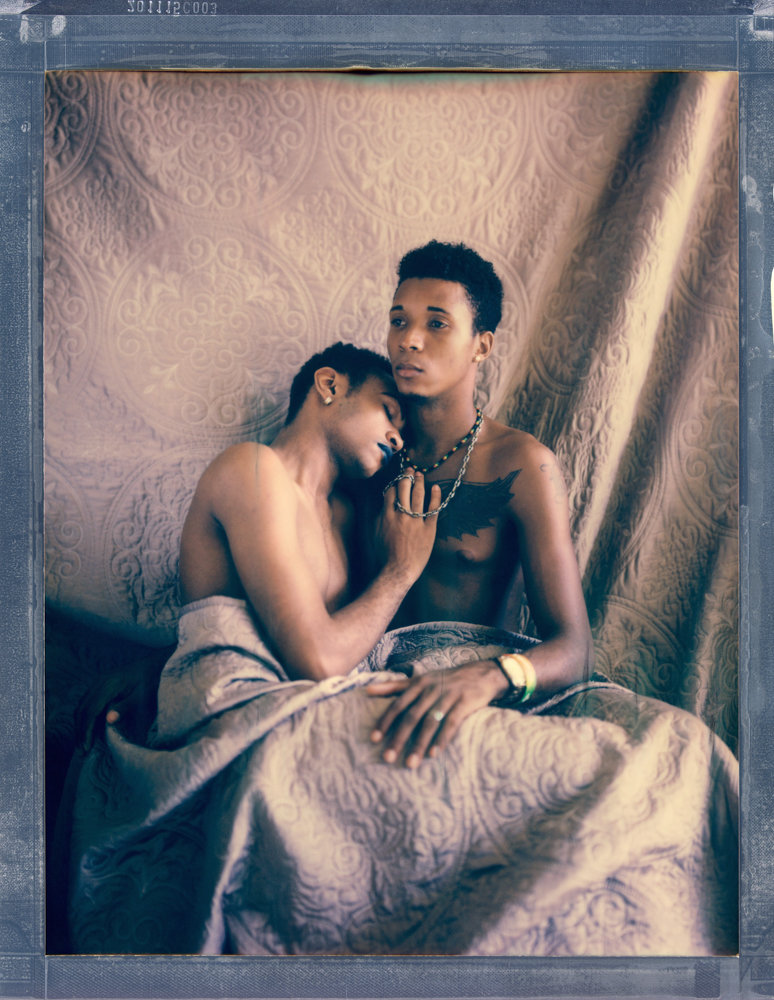

Whereas photojournalism typically requires its practitioners not to intervene in the making of a photograph, Hammond found that he had to rethink his approach with the people in “Where Love is Illegal,” given the sensitive nature of their stories and the precarious conditions they live in. He opened up his process, inviting the people in front of the lens to collaborate in the making of their portraits.

“The way that they are seen, for many of them, is fundamental to who they feel they are,” Hammond said. “They are very conscious of how they are represented.”

By making the process collaborative, Hammond provided a space for LGBTQ people to have greater agency over their own narratives, which is something Hammond realized had been lacking in news coverage of that community.

“Very rarely did we hear from people at the heart of the issue,” he said.

The images themselves show people in spaces where they are the most comfortable, usually in their homes. What is not shown is the discrimination and oppression they face on a daily basis.

There are subtle forces at work in each photograph. They are remarkably beautiful in how they celebrate each person’s identity — and in some cases, a couple’s loving relationship — but there is an undercurrent of sadness in the circumstances surrounding each picture.

Hammond found people often were willing to show their faces, although there are instances in which they could not. It was a decision borne out of a concern for their own safety, but it is at the same time a powerful aesthetic choice.

It reveals just as much, if not more, than it conceals. By concealing their faces, they reveal the political, societal and cultural forces that make showing their faces such a dangerous proposition.

“Sometimes it’s unexpected how they will present themselves,” Hammond said, “and it goes against my journalistic instincts.”

In 2015, he met Jessie, a transgender Palestinian woman living in Lebanon. She told him a harrowing story about how her family had tried to kill her, and with that in mind, he initially sought to photograph her in a way that reflected that. Yet, that wasn’t what she wanted.

“She wanted to present herself as this sexy young woman,” Hammond said.

In her photograph, she wears a floral and paisley print shirt with a red scarf obscuring most of her face, except her eyes. She gazes intensely into the camera. Hammond found that her choice better suited the picture and her story.

“She’s not just that horrendous experience,” Hammond said. “She’s more than that.”

In the years since beginning the project, Hammond created Witness Change, a nonprofit organization that seeks to “end human rights violations for marginalized communities through visual storytelling.” This also spawned a social media campaign for “Where Love is Illegal” that has since accrued nearly 200,000 followers on Instagram.

It features Hammond’s original photographs as well as submissions from LGBTQ people from around the world.

It is a testament to photography’s inherent power to raise awareness. Photography’s ability to effect change, however, is another matter.

“Sometimes there are images out there in the world that have made a measurable impact,” Hammond said. “And I just don’t know if these are amongst them. But I keep hoping that it can work toward a better future for these people.”