Reviving truth of civil rights icon

Rebecca Brown-Barbier gestured everyone back into a room at the Riverdale Library she runs. Parents and children congregated into the small performance space and almost immediately fell quiet.

The audience was greeted on the stage by fifth-graders with something very important to share: Two major civil rights speeches by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., with selections by fellow activist and wife, Coretta Scott King. All in celebration of the civil rights icon’s birthday.

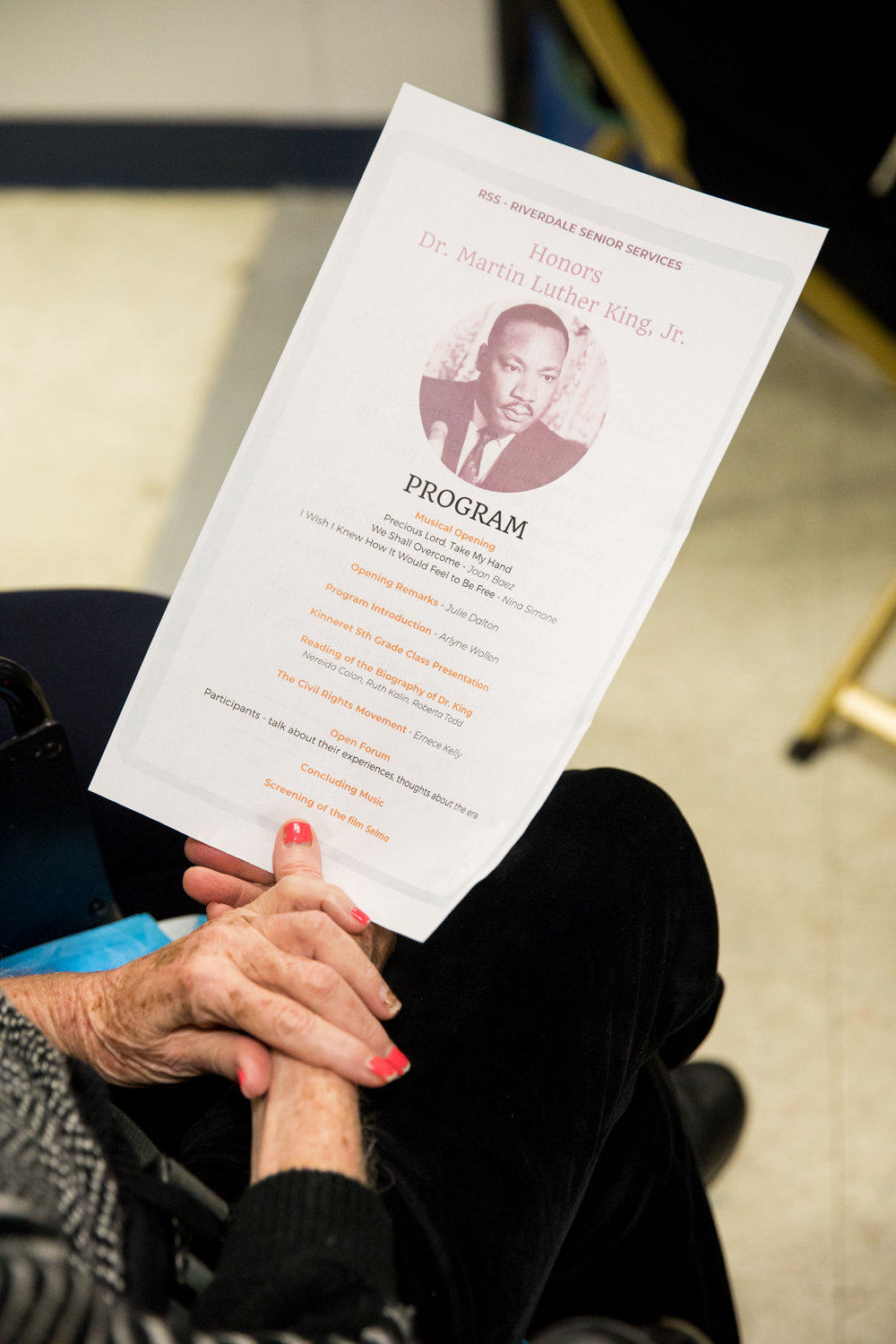

Not far away, at RSS-Riverdale Senior Services on Netherland Avenue, civil rights activist and academic Ernece Kelly presented a speech of her own talking about her former boss, Dr. King, and his work in Kelly’s hometown of Chicago during the summer of 1966.

“I was a junior college teacher,” Kelly said. “But I noticed my closest friends were volunteering and participating in more activist work, so I went, too. Five months later, King arrived, and it changed my whole life.”

Kelly’s memories include scenes of grand action and movement: King taking up residence in a “slum apartment” in Chicago’s west side, while galvanizing neighborhoods and leading protests — silent and thunderous — against then-mayor Richard Daley.

Kelly’s work was not at podiums, but instead behind the scenes. She distributed flyers, organized meetings and rallies — all important, but unglamorous, work during a summer known for its powerful pageantry. The Coordinating Council of Community Organizations, the activist group Kelly worked for, represented the marginalized in Chicago and their demands, even before King’s arrival.

“Chicago was highly segregated,” Kelly said. “Al Raby and the CCCO rallied for housing, for integrated schools, for things that black people couldn’t have at that time. In ‘66, Raby got King’s help. Then people were watching. He had a whole toolkit of strategies that used marches, rallies, picket lines, you name it. He held the largest civil rights rally at that time: 60,000 people.”

In Chicago, and throughout his career, King had backing from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and needed help from people like Kelly to succeed in raising to keep these rallies and marches going.

“That’s not something that’s really discussed in schools,” Kelly said. “One of the most distressing aspects of today is that King’s memory is being revised. He is now only ‘the dreamer,’ something static and detached. His legacy should be about political activity and change.”

Delores Dixon, former member of The New World Singers folk group who marched on Washington with King, regards the state of King’s legacy in schools to be even worse.

“He’s not really discussed,” Dixon declared. “I’m a retired teacher. People look at each other and say, ‘Oh, we’ve got tomorrow off, why’s that?’ King’s birthday is just a day off for some. He gave up his life for this land and its people.”

King’s work, Kelly maintained, was for the disenfranchised, which meant bringing together all people regardless of race. King’s work was for the raising up of black people, but also for the unity of all who were poor. His efforts with the Poor People’s Campaign, for example, was the culmination of that hope.

“Schools need to show how much there is to learn about Dr. King,” Dixon said. “The Poor People’s Campaign was his last dream, and they don’t really talk about that.”

At the Riverdale Library, some of the children recited King’s famous Lincoln Memorial speech “I Have a Dream” and “The Other America” with the unrefined, yet rhythmic, cadence of children reading aloud horrors experienced as though reciting a hazy dream.

Others, however, read with the rage inherent to King’s words. That wasn’t just instinctual. Julissa Ayala and Angela Switzer, the Mosholu Avenue facility’s young adult librarians, rehearsed those speeches carefully with the students.

“We went through the definitions, we talked about his cadence and his projection,” Ayala said. “I hope they experienced it rather than just learned about it. In a classroom, words are just thrown at you.”

This was the first year the group included selections by Coretta Scott King to further de-mystify the memory of King.

“We don’t even talk about how Coretta edited and co-wrote a lot of her husband’s speeches,” Switzer said. “Education takes for granted that kids are getting information about him from other sources. We don’t talk about his being arrested in Birmingham, or John Lewis and Coretta Scott King being chased out of Forsyth County in Georgia. He’s become this myth.”

The librarians maintain that because children are young, they should learn slowly. But the fact remains that, eventually, they’ll have to learn.

“We’re taught racism is bad,” Ayala said. “But we aren’t told how insidious the system is. How it continues to be.”

Kelly herself utilizes a unique method to ask children an important question, one that may make them realize the importance of King’s birthday.

“When I talk to especially young people,” Kelly said. “I use this Waldo book. I say, ‘Yeah I know it’s hard to find Waldo in some of these pictures. It’s hard to find Dr. King, too. Where do we find Dr. King on his birthday?’ We find him in demonstrations at racist institutions, at fast food restaurants where people demand $15 an hour.

“That’s not too much to give these people who are struggling. That’s where we find Dr. King today.”