Ziering archive honors Holocaust's survivors, fighters

Holocaust survivor and Nazi hunter Herman Ziering was dedicated to memorializing those who died in the Holocaust, and bringing those who were complicit to justice.

His daughter Debby found out just how dedicated not long after he died, sifting through boxes of his belongings. It was there she found reams of documents related to World War II and the Holocaust.

Those included the travel documents his family used while they were moving to the United States after the war, telegrams sent across the United States discussing the Holocaust, and even a letter from famed British prime minister Winston Churchill discussing the resettlement of Jewish refugees in Palestine.

“My dad was a survivor,” said Debby, his oldest daughter. “He survived because he learned to wheel and deal, and he took things he wasn’t supposed to. That’s how he learned to live. That’s how he got those documents.”

Finding value in history

Debby didn’t just want to move the papers from attic to attic. There was value here — just not the financial kind. She started reaching out to nearby synagogues and Jewish centers. Most of them offered to store the items, but Debby was looking for more.

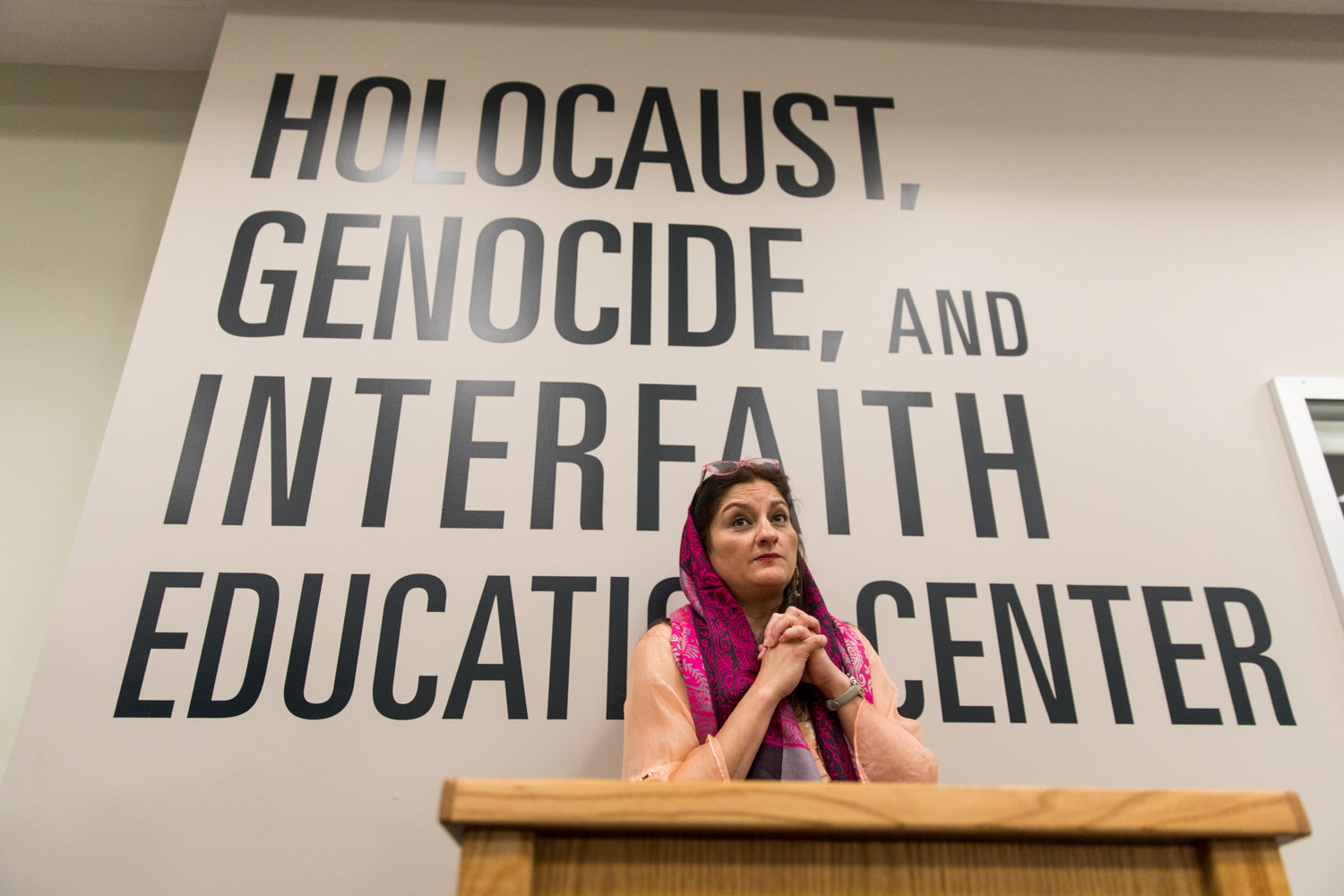

That’s when she found the Holocaust, Genocide and Interfaith Center at Manhattan College. She took a meeting with Mehnaz Afridi, the center’s director, bringing along a box of her father’s belongings.

Afridi was running late that day, and the two didn’t get a chance to talk. But the professor did take a moment to sift through Herman’s box. When Afridi found inside amazed her.

“I said, ‘Do you know what you have?’” Afridi said.

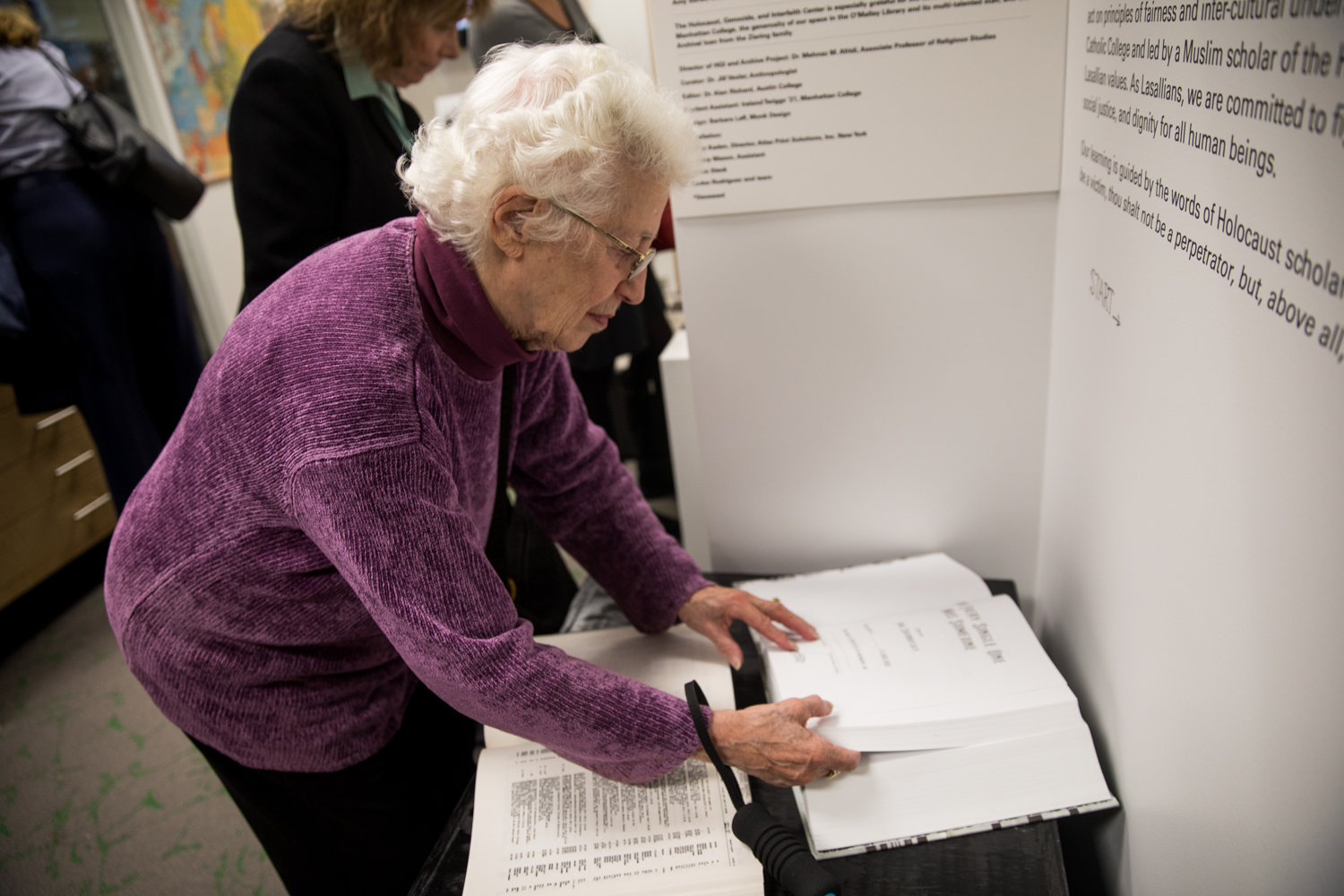

Debby brought more boxes in, and Afridi knew this material couldn’t be hidden any longer. She started working with the center’s board putting together an exhibition.

“I thought we’d display a few papers, some books,” Afridi said. “I didn’t think it would be a real exhibit, like a museum-type thing.”

That “real exhibit” opens Nov. 12 as the Herman and Lea Ziering Archive Collection, showcasing the histories of Debby’s parents as part of the larger Holocaust narrative.

Visitors can leaf through books dedicated to the Riga Ghetto, including one from a meeting of survivors, which memorializes each person who died. A book called “And Every Single One Was Someone” contains the word “Jew” six million times to represent the number of Jewish people killed in the Holocaust.

Building a survivors’ community

Herman never slowed down when it came to working closely with other survivors and organizations that dealt with survivors. In fact, it was a sort of coping mechanism, Debby said, for dealing with what he had lived through in his childhood.

“They would kind of sit around and make camp jokes,” she said of her father and his friends. “All their friends had accents, they would get together — either through the ghetto organization or socially — and they had this common bond. People who haven’t gone through it can’t understand.”

Ziering was part of the Anti-Defamation League’s task force on Nazi war criminals, working to expose Boleslavs Maikovskis, who served as the police chief in German-occupied Latvia, where Herman was from. Maikovskis had moved to the United States after the war and settled in Mineola. He had been stationed in Kaiserwald while the Ziering family were there during the war, Debby said, and shot a friend of Herman’s mother.

Maikovskis fled to Germany in the 1980s after it was clear he was going to be deported to the Soviet Union, according to published reports. He died in 1996 after German officials suspended his trial because of his age.

“That was the first person they went after,” Debby said. “That kind of ignited the spark to pursue this.”

A clipped-out article from Newsday shows Debby’s sister, Mia, holding a sign outside Maikovskis’ house, part of a protest calling for him to be tried and deported.

“I was in fifth grade, being taken out of school to go protest,” Debby said. “The night before, they were making signs in our house, and it was a big to-do.”

In honor of Herman’s work, student docents working at the advanced opening of the Manhattan College exhibit Nov. 6 wore T-shirts emblazoned with “HGI Nazi Hunter.”

“I wanted my students to be empowered, they want to bring people to justice,” Afridi said. “It’s the most important thing they can do.”

Afridi hopes the exhibit is more to visitors than just a collection of things from Herman’s life.

“I wanted to honor him, his family, and honor the fact that there were people who really just wanted justice at the end of the war,” she said.

There also was a larger theme for the young people in Afridi’s class, all of them born decades after not only the Holocaust, but even the efforts to hunt down Nazis around the world.

“I think the most important thing for my students is to have a critical lens and question what’s going on,” Afridi said. “We really didn’t do much in terms of the Holocaust, it was only at the end that the U.S. got involved. Genocide is still occurring, there are ways to intervene. Not just with sanctions, but with demilitarization. A lot of countries only intervene out of self-interest.”

Remembering, and never forgetting

Debby hopes the exhibit serves as both memorial and a warning for those who visit.

“I hope it makes them aware of what’s going on today,” she said, “and it certainly could happen again.”

It’s also a place to remember her parents, who, despite everything, were full of life and brought their children along on their adventures.

“My dad loved to play jokes on people,” she said. “In the snootiest places, he would take out a plastic ice cube with a cockroach in it and put it in a drink. He loved getting reactions from people.”

The older Zierings were still serious in ensuring their children were aware of the realities they had faced.

“The message to us always was, ‘There might be a day when you need to leave. All this that you have might be gone, because that’s what happened to me.’ He wanted us to try to appreciate every day, and realize that it was possible that it wouldn’t be permanent,” Debby said.

Ultimately, Debby is happy to tell her father’s story, sharing what he did for the world.

“As the child of a survivor — and it’s not just me, it’s many children of survivors — you’re taught not to reveal too much, and to be careful about what you say,” she said. “Having this exhibit about myself, I do feel like it’s revealing a lot. But I think my dad did amazing work, and there are so many amazing lessons that can be learned.”