Learning to cope with autism

CORRECTION APPENDED

A Press special report by Kate McNeil

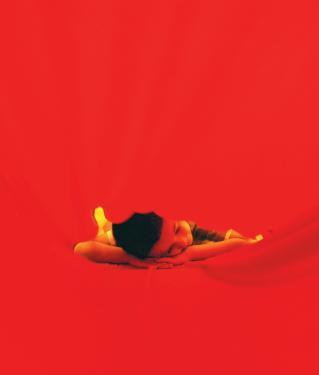

It's a Sunday at Seton Park. Rainbow-colored birthday balloons sway in the breeze. "Happy Birthday Devin," reads the red frosting on the Spiderman cake softening in the sun.

Devin Ranallo is 5. The boy's wide eyes focus on the Power Rangers that must be hiding in those colorful boxes at the end of the table.

As his mother, Francine Szymanski, watches her rambunctious boy blow out his candles, she thinks of September.

Devin is a kindergartner-to-be, and Ms. Szymanski worries as she looks ahead to the first day of school. In May, her smiling son was diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome, a type of autism.

For parents of autistic children, the closest thing to a "cure" is a maze of schools, a labyrinth of Web sites and a jumble of costly therapies.

It's no wonder the symbol of Autism Speaks, the nation's leading nonprofit organization devoted to autism, is a single piece of a jigsaw puzzle.

The puzzling disorder is in the limelight these days. And rightfully so: in February, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that one in 150 children has been diagnosed with autism, compared to one in 10,000 in 1993.

Last year, 5,680 children diagnosed with autism enrolled in New York City public schools, nearly twice as many as five years ago, according to Maibe Gonzalez, a spokeswoman for the city Department of Education.

Within Community School District 10's boundaries, which include the Riverdale-Kingsbridge area, 203 students with autism have enrolled at a school in District 75, the city's special education district. Thirty-eight autistic students attend special education classes at local schools. And these are just the children with a formal diagnosis like Devin's.

Autism, said Riverdale physical therapist Andrea Schloss, has reached "everybody-knows-somebodywith- it" proportions.