The Freeman identity: Spuyten Duyvil centennarian was a master spy

Spuyten Duyvil centennarian was a master spy

By Tommy Hallissey

Shhhh! Albert Freeman may be listening. During his 100-year lifetime, the Knolls Crescent resident has heard a lot - and he has shared much of what he has learned with both the FBI and the Soviet Union.

A committed communist in his youth, he set up spy stations all over Europe for the Russians, but for more than three decades in his later years, Mr. Freeman helped the FBI intercept Russian secret messages. Ironically, Jack Childs, the man the communist party assigned to check up on Mr. Freeman was himself an FBI mole.

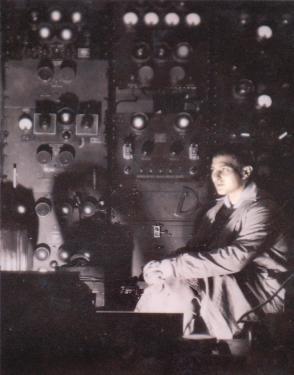

Born in Manhattan on Sept. 11, 1907, Mr. Freeman developed a close bond with his Russian-born father, Boris. His formal schooling never extended to college, but his father was a chemical, electrical and radio engineer and he shared his knowledge with his idealistic young son. A stint working with the Radio Corporation of America taught him Morse code and helped to hone his skills.

Still a teenager, Mr. Freeman joined the Comintern, a Moscowbased organization dedicated to the overthrow of capitalism. During the 1920s he traveled throughout Western Europe teaching members of the communist underground how to set up and use clandestine radio transmitters and receivers.

His wife, Gerta, was a Jew and a Communist Party member in Vienna when he met her in 1935 as the Nazis were rising to power. He brought her safely to America in 1938.

"I followed him wherever he was," Ms. Freeman said delicately.

The couple was married in 1941 in Virginia by a drunken justice of the peace. They chose the out-ofthe- way location for the ceremony because they worried that someone might recognize the picture of a communist spy in a newspaper wedding announcement.

But by this time, Mr. Freeman had become disillusioned with communism. His father had returned to Russia, but once there, he was told that he was too valuable ever to be allowed to leave the country. "He knew too much," said Mr. Freeman.

He tried repeatedly to get his father out of the Soviet Union. He was able to free others of the grip of communism, but never his father. "Was I pissed off and they knew it!" he exclaimed.

That betrayal fueled his drive to become a secret agent. "That's the chief reason," he said. "They wouldn't let my father go free. [I was determined that] they would be the last to win the Cold War."

But it would be years before he was able to offer his skills to the FBI. World War II intervened and Mr. Freeman enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps. He served honorably as a photographer from 1942 to 1947.

At the height of the Cold War, Mr. Freeman got his chance to become an American secret agent, but he preferred to remain a freelancer. He felt he had more freedom without a long-term commitment. "He was hounded by the FBI," said Ms. Freeman. "They wanted his talents."

Mr. Freeman recalls that the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 in Dallas, Texas, profoundly affected him and propelled him to establish an ongoing relationship with the agency that lasted until 1991.

His first order of business was to take an oath and sign a paper that said if he revealed any secrets he would be subject to an $11,000 fine and 11,000 years in prison.

From his days as a Comintern agent, Mr. Freeman - now code named Clip - had contacts with Gus Hall, a Riverdalian, who was the head of the Communist Party USA. He set up a receiver in the bedroom of his Knolls Crescent apartment to receive Morse code from Russian operatives in America. Unbeknownst to Mr. Hall, his encoded messages, were also forwarded to the FBI. Mr. Freeman never knew what they said.

The beauty of the operation, from a workingman's perspective, was that both the Americans and the Russians had Mr. Freeman on their payroll. A man would show up at his door say a code name and give him an envelope.

Mr. Hall received countless messages from Mr. Freeman. On occasion, they would meet in person and Mr. Freeman would wear a wire. "Every time he went I was shivering," said Ms. Freeman.

Both Freemans disliked Mr. Hall very much. They said Mr. Hall "thought he was an Adonis" and was "so chintzy." Once, Mr. Freeman went out to dinner with Mr. Hall and his family. Mr. Freeman picked up the check and the U.S. government reimbursed him, in effect paying for a meal for the head of the Communist Party USA.

Harry Pollitt, the head of the Communist Party of Great Britain, was another of Mr. Freeman's contacts. Mr. Pollitt's secretary met him in England and gave him a kiss on the cheek. "What the hell is this for?" he recalls saying.

"You are going to work with me," she replied. As she escorted Mr. Freeman through the streets he saw her kiss a couple of other men on both cheeks. Years later Mr. Freeman still wondered, "If I'm supposed to be kept secret, who are these agents knowing about me?" And he insists Mr. Pollitt was a double agent, too.

Twenty-six years after Mr. Freeman's retirement, virtually all of the agents he worked with are dead. Jack Childs, the first agent to contact him, was immortalized in a book 11 years ago. But not until now has Mr. Freeman come forward to claim his recognition for being a secret agent during the Cold War.

While Mr. Freeman says he trusted no one, the Russians, he said, never suspected he was passing on messages to the Americans. "I was already concerned, but you can't call it scared. I wouldn't have done it then," he said. "I'll give you news," he added, "everybody was an agent."