Homeowners gird for zoning battle with developers

The winds of March gusted through the neighborhood as Marisol Jimenez rolled her wheeled bag along the hilly streets leading to her Webb Avenue home.

Jimenez is new to this part of the Bronx south of the Jerome Park Reservoir, moving in November 2016. She’s surrounded by quaint four-, five- and six-story buildings, with concrete patios hidden behind wrought iron gates. Nearby, a weather-beaten figurine of the Virgin Mary stands guard in front of one home, peering out at the sidewalk.

“It’s a very quiet neighborhood,” she said. “We pretty much keep to ourselves, unless it’s dealing with teenagers and children (we’ve) known.”

Yet Jimenez’s journey to Kingsbridge Heights isn’t one filled with fond memories. She was practically forced from a home she maintained in Bedford Park since the mid-1990s, all because a developer wanted to replace her two-story home with a residential tower.

Coming to this neighborhood was supposed to get her away from all that. But as developers continue to look up (and north) for more higher-density development, Jimenez fears those problems may have followed her here.

And developers already have an advantage in this part of Kingsbridge Heights — much of it is already zoned for the kind of high-rise towers they’re looking to build.

What to do, what to do

Community Board 8 just recently renewed its focus on this part of Kingsbridge Heights, an area around Webb Avenue between West 195th and West 197th streets just south of the Jerome Park Reservoir.

Charles Moerdler, the longtime chair of CB8’s land use committee, was once a resident of this very community, living on University Avenue when he was first married some 60 years ago.

“My kids were born there, and that block was once an absolutely gorgeous block,” Moerdler said at a recent land use meeting. “But it’s an area that has been allowed to really drift.”

The neighborhood, Moerdler said, was once a garden spot of the borough. And he believes it can be once again.

But not with current zoning, which could allow the homes — many with Mediterranean-style barrel tile roofing, meticulously detailed fences and columned balconies — to be replaced by high-density towers.

One way to stop that is with rezoning — a downzoning, actually, which would force anyone building in this neighborhood to stick to what’s already there. But spot downzoning is illegal, Moerdler said, and convincing city officials to cast a wider net in downzoning the larger community is an almost impossible task.

It’s exactly what Jimenez and her neighbors were fighting for in Bedford Park.

Eight years ago, residents there petitioned the city planning department to uniformly downzone the neighborhood, limiting building heights to five stories, instead of the 10 — or even 13, in some cases — stories that were currently allowed in parts of Bedford Park.

But those concerns fell on deaf ears, and did nothing to discourage developers from pursuing plans to build upward.

It all came to a head in 2016 when Queens-based developer Peter Fine ordered residents of 267 E. 202nd St., a small but aging two-story home, to move out within 30 days. Fine reportedly planned to take that site and an adjacent parking lot and transform it into a 12-story apartment building.

The protracted legal battle that emerged would become symbolic of Bedford Park’s downzoning effort. That was until the wee hours of Aug. 11, 2016, when the East 202nd Street home went up in flames, injuring 10 and killing a family dog — a fire later blamed on a broken air-conditioner.

“We lived in there since 1995,” Jimenez said. “And we said, ‘Wait a minute. You can’t just dispossess us like that. We’re not pets, you know. We’re people.”

Fine later settled with the tenants, but when it comes to neighborhood zoning, nothing has changed in Bedford Park.

Rich in history

Moerdler’s memories of this section of Kingsbridge Heights goes back decades, but its history extends even further. In fact, long before people lived in Kingsbridge, the community was a backdrop to American history.

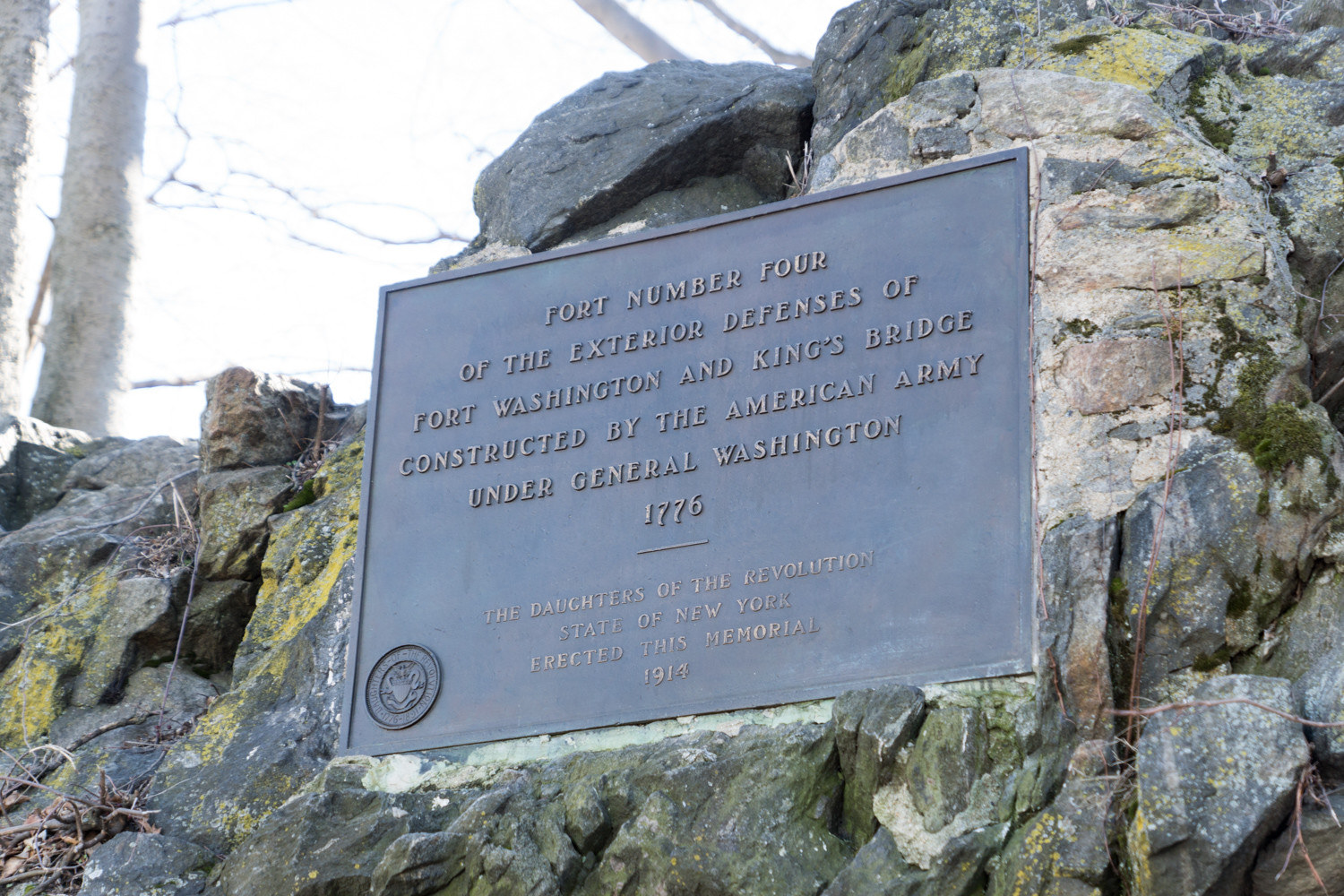

During the Revolutionary War, Fort Four was built between University and Claflin avenues, designed to protect both the Continental Army and the Harlem River.

Later, merchant Horace Claflin built a summer home for his family there — known as Claflin Manor, overlooking what was then the Jerome Park Racetrack. Not only were horses raced there, but one of the sport’s biggest races — the Belmont Stakes — ran there between 1867 and 1889.

The racetrack itself was shuttered a few years later to make way for the Jerome Park Reservoir, needed to help supply a fast-growing New York City.

By the time Peter Ostrander was growing up along Webb and Reservoir avenues in the 1950s and early 1960s, things were a bit different.

The neighborhood was filled with blue-collar working class families, and Ostrander — now the president of the Kingsbridge Historical Society — was able to catch glimpses of the reservoir from his bedroom.

Living in this part of the city at the time was like living in the country.

“You were isolated from the train because you were at the end of everything,” Ostrander said “The No. 4 was a hike. But at the end of the block, you had this almost like inland sea or ocean that was the reservoir.

“It’s huge when you think of it. It’s (an immense) body of water to have at the end of your block.”

Stopping vertical development in the neighborhood? “I think it’s a good thing,” Ostrander said. Otherwise “everyone would be on top of each other.”

Driving people out

Daniel Barraza has lived in this pocket of Kingsbridge Heights for 24 years, a place where there isn’t a lot of drama, he said, while standing in front of his West 197th Street building.

“Besides the drugs,” he quickly added. “Not a lot of traffic. It has its bads and its good,” although lack of parking is a major issue.

Barraza was unaware the neighborhood’s lower-density homes could easily be replaced with towers. But then again, he isn’t against it — especially if it means more affordable housing.

“Me and my wife have been looking for a low-income apartment,” Barraza said, “and it’s very hard. They just going to build more buildings? Hey, go ahead. I’ll go for that.”

CB8 chair Rosemary Ginty, however, isn’t going for that.

“People know how beautiful that street is, and it is a very special street,” Ginty said at a recent land use meeting. “This is a pretty high zoning for this part of the Bronx, and there is economic incentive to knock down those homes.”

Yet Ginty, who has spent much of her career working with and for government, knows how hard protecting this particular neighborhood will be.

Downzoning is a viable option — but only if they can convince the city to do it.

But there might be another option that seems to be working in Country Club, a small enclave overlooking Long Island Sound, where the state has declared it a “non-solicitation real estate zone.”

That designation, according to a September story in the Norwood News, creates a list similar to one telemarketers must abide by when trying to sell something over the phone. Homeowners who add their name to a “no solicitation” list in a designated area can legally prevent developers and Realtors from paying you a visit out of the blue.

Building taller towers requires a wider footprint than many of the current lots that exist in communities like Kingsbridge Heights. Even if one property owner decided to sell, a developer would need to acquire some of the surrounding lots in order to have enough land to build on.

Without this “cease and desist” designation, those developers are free to contact the neighboring homeowners — even if their property is not on the market — and try to convince them to leave. With the designation, developers could only reach out to those neighbors if they, too, were already looking to sell.

If there’s no way to accumulate property, there is no way to plan high-density developments, and zoning or no zoning, neighborhoods are shielded from change.

The problem is convincing state leaders this particular neighborhood deserves that same kind of protection. CB8 must demonstrate the area has been bombarded with “intense and repeated” solicitation, according to published reports. Simply anticipating future development may not be enough.

But something must be done, Jimenez said, and she’s looking for local and city officials to do something about it.

“Let’s talk English,” Jimenez said. “I know what gentrification is. That’s what (developers) are trying to do.”

Downzoning, although difficult, “would give them a hard time,” she added.

“I don’t know if we can stop them, but we’re going to damn well try. Because what they’re literally doing is driving people out of their homes, in a legal way.”