Over a shared meal, Muslims look inward, outward

As the sun approached the end of its shift on a Tuesday evening, watermelon slices and dates occupy plastic foam plates on a blue tarp at the Islamic Center of Yonkers.

The hot food was set up on a table at the back of the mosque and the sense of anticipation was palpable. The disappearance of the sun meant those in the mosque could finally eat.

It was nearly time for iftar, the meal breaking the daily fast that’s part of Ramadan — a holy month quickly approaching its end.

Those in the mosque spent the entire day fasting, as is the ritual during Ramadan. The weather had yet to get really hot, but fasting was no less arduous. The prospect of iftar was a relief, and the scents of chicken, rice and vegetables wafted from their containers.

“I’m having fun, a lot of fun, with Ramadan. I think I am losing some weight,” joked Imam Adam Adamu as he patted his stomach.

On the face of it, Ramadan may seem purely a physical challenge. But the reality is that it is as much mental and spiritual as it is physical.

“Your job is to do what is right,” said Tariq Tahir, a longtime member of the mosque who came to the United States from Pakistan in 1973.

Ramadan is more than just abstaining from food and drink. It presents a challenge that goes beyond the physical. It requires Muslims look both inward and outward, to extend a hand to those less fortunate, and offer help.

Fasting is not exclusive to Islam, but Islam does present arguably the most challenging form of fasting. From sunrise to sunset, eating and drinking is typically forbidden. And for the last 10 years — in the northern hemisphere at least — Ramadan has coincided with summer. Longer days require greater discipline, like running a marathon, which is how Imam Adamu spoke about it during a Friday prayer in mid-June.

“In these last 10 days, we are already in Manhattan on Fifth Avenue,” he said, likening the final stretch to the route of the New York City Marathon.

Once the call to prayer resounds throughout the mosque, everyone breaks their fast with dates, which is how the Prophet Muhammad is believed to have broken the fast. Lids come off containers, steam rises, and food piles onto plates. Children dart around the mosque as food is served.

“Let me take a picture,” a young boy named Yahya said reaching for the camera of a photographer attending iftar that night. He turns the camera toward his friends, pressing the shutter. He then takes off in favor of a plate of food.

Ramadan is the great leveler, a coming together of the Muslim community worldwide. To break bread with someone is to share something truly sacred. The communal experience of iftar runs counter to commonly held views about Muslims in the wake of tragedies.

In London, when a fire eviscerated the Grenfell Tower, some of the first responders were Muslims who happened to be awake because of Ramadan. The fire broke out shortly after 1 a.m., and Muslims were among the first to notice it as they were preparing their last meal of the night, and helped save lives, according to The Telegraph.

The Muslim community in America has come under increased scrutiny since the advent of the current administration, particularly with the first attempt at the travel ban in January that halted immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries, sparking a nationwide series of protests at major airports. In 2015, when Donald Trump was still a candidate, he called for a “complete and total shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” following the attack in San Bernardino, California.

Islamophobic rhetoric has put Muslims at the front of the national dialogue. Yet despite this, they are carrying on as usual. Perhaps the strongest response to oppression is to persist, to continue with one’s rituals as though nothing is actually happening.

“I’m always mindful that the world is the world,” said Andre Taylor, a member of the Islamic Center of Yonkers, whose chosen name is Abdul Noor Ibn Taylor. He goes by both.

For Taylor, even though the president may take a hard line stance against Muslims, Ramadan is no more or less important than any other year. The tenor of the month is the same, as are the rituals.

After people finish eating, they move to the main prayer space for the day’s final prayers. And just like any other day, men, women and children from New York and elsewhere join in the ritual.

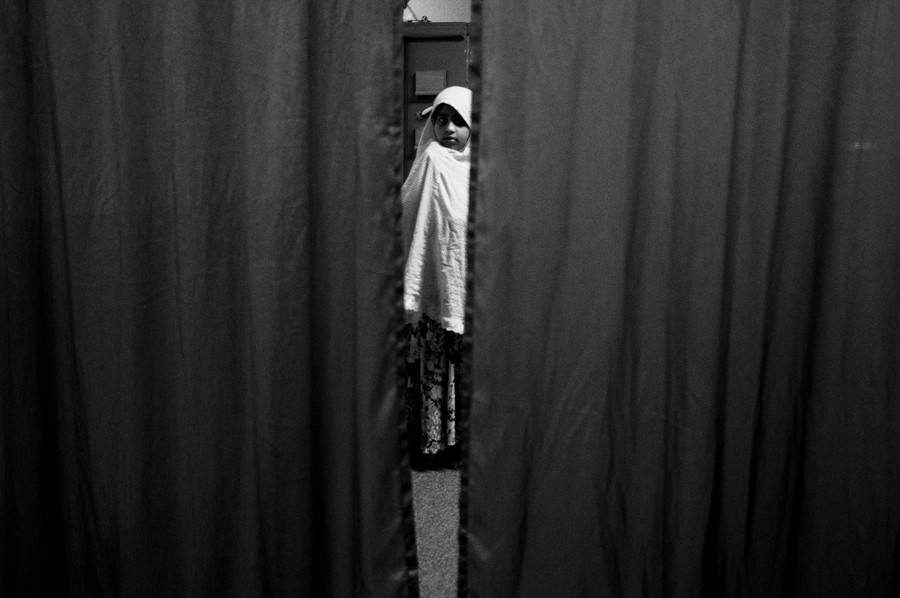

When the main area became too full, people took up spots in the entry hallway. That’s where Suraiya, a young Bangladeshi girl in a pink hijab, found herself praying and fending off the tumbling antics of her toddler cousin Zarif whose boundless energy wouldn’t allow him to sit still.

As the service wound down, people filtered out of the mosque to get a full night’s sleep. And begin again the next day.