Lending a hand in Krakow from Riverdale

How a kosher meal brought two locals together in midst of war refugee crisis

Lauren Calihman found herself walking the winding streets of Krakow in search of a kosher meal. The food wasn’t for her, but for an Italian man who’d come to Poland last month during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Calihman, who lives in Spuyten Duyvil, had flown to Poland in early March — which has taken in more than 2 million Ukrainians since the war began — to help out with the refugee crisis in whatever way she could.

On the night of March 14, that meant finding some kosher grub.

Yet Calihman was coming up dry. She doesn’t speak Polish. She doesn’t speak Ukrainian. She knew enough about Krakow to venture into the old Jewish quarter of the city, but beyond that, she was flying by the seat of her pants.

Still, she was determined.

That’s when she spotted a man walking in the opposite direction wearing tzitzit, religious fringes worn by observant Jews. Her luck had changed, she thought. Surely this man can point her to Krakow’s equivalent to Liebman’s Deli.

“I just stopped him, and I said, ‘Do you know, where I can find a kosher place?’” Calihman said.

Alas, no dice. In fact, the man was just as unfamiliar with Krakow’s streets as she was. He had just taken a flight from the United States to Poland days ago to help out Ukrainian refugees, just like Calihman.

He introduced himself though — his name was Shabbos Kestenbaum. He was from Riverdale.

“We’ve never crossed streets in Riverdale or met each other. And yet we crossed paths in Krakow,” Calihman said.

“So we both kind of freaked out,” Kestenbaum added. “Then from there we were like, ‘OK, let’s partner up.’”

So they did. And that night, after about a half hour of searching, they were able to score some elusive kosher meats at, what Calihman called, a kind of speakeasy in a back alley of the town’s historic Jewish quarter.

“There was just this random apartment with this guy who gives people kosher food for free at this gigantic banquet table,” she said. “The Italian guy was happy. I was happy. Shabbos was happy.”

Taking a leap of faith

In the first few weeks of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, both Kestenbaum and Calihman were mere blocks away from one another in the Bronx, watching the refugee crisis unfold in the news. Day after day, thousands upon thousands of Ukrainians poured into Poland, their lives entirely uprooted.

At the time, both Kestenbaum and Calihman were doing their parts — donating to relief funds, signing petitions, protesting — but they felt as if they weren’t having enough of a direct impact.

“When there’s some sort of crisis or emergency, I really like to get involved — get my hands dirty — rather than being a spectator on the sidelines,” Calihman said.

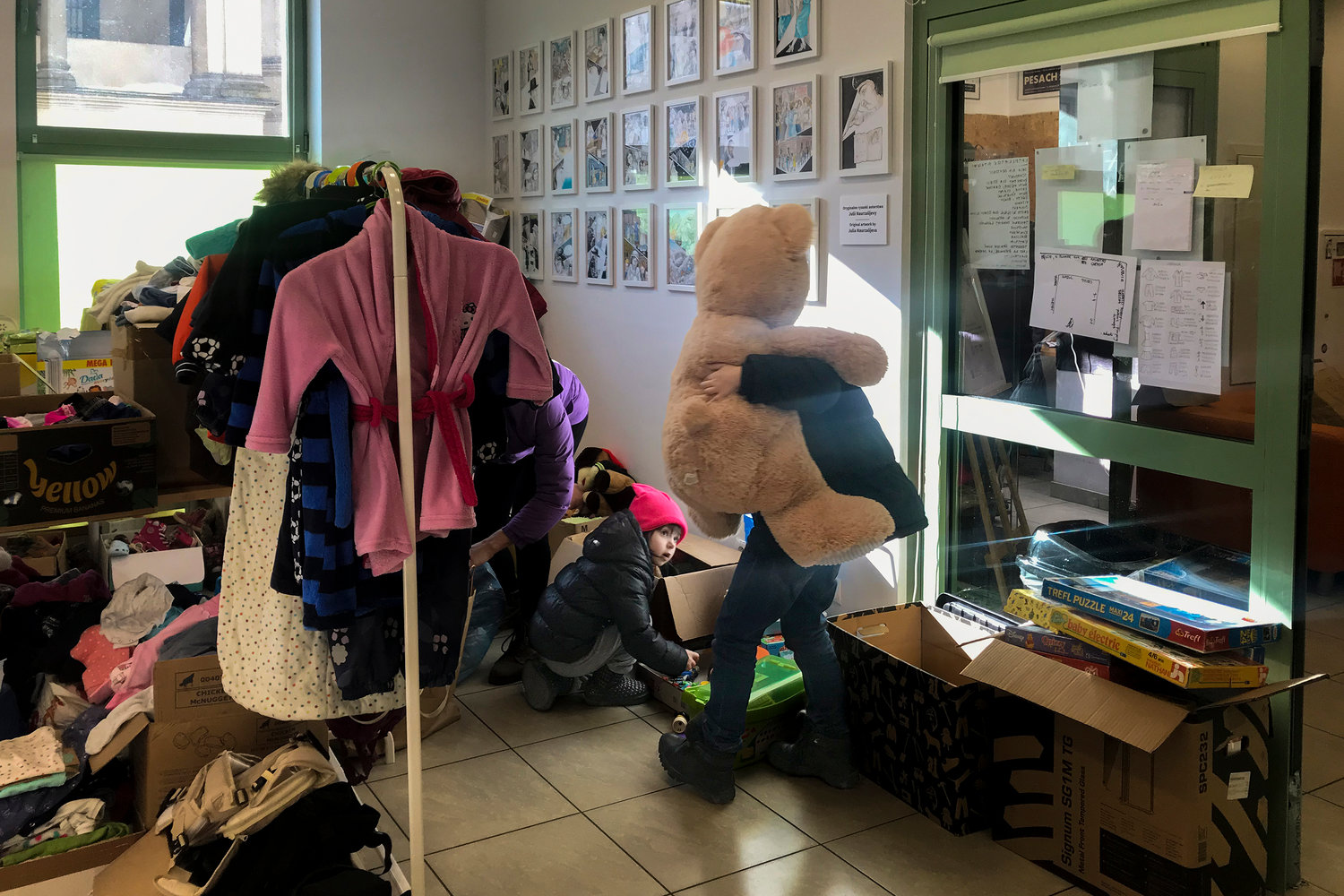

After emailing everyone she knew, Calihman got in touch with the head of the Jewish Community Centre of Krakow, who invited her to come volunteer. Since the onset of the war, the Krakow JCC has served as a 24/7 support center for those fleeing the violence.

On March 8, Calihman caught a plane to Poland, bringing four suitcases packed full of women’s sanitary products, toiletries, and any other donation she could stuff inside.

Kestenbaum, for his part, just took a leap of faith and bought a plane ticket.

“I quite literally just showed up,” he said. “I just showed up at the JCC Krakow and said, ‘What can I do to help?’”

After their cosmic kosher excursion, the two spent much of their time at the JCC providing logistical support. Seven days a week, if refugees needed a meal, clothes, lodging, toiletries, a cell phone, travel arrangements — you name it — they could go to the JCC where dozens of volunteers, from both Poland and abroad, would try and help.

“You’re meeting families who came with one suitcase, if they were lucky,” Kestenbaum said. “People whose homes have already been bombed, or they don’t know what its condition is. Their kids haven’t had a real life in weeks. And it’s very, very difficult.”

When they weren’t volunteering at the JCC, the duo found other ways to make themselves useful. Calihman would visit transit hubs, looking for refugees in need of a place to sleep. On Purim, Kestenbaum played guitar for a group of Ukrainian children and checked in on refugees in hotels to make sure they were able to fulfill the holiday’s requisite religious obligations.

‘We need to come back’

At one point in their time abroad, the two even chauffeured a Ukrainian religious leader to the war-torn border.

On March 15, Calihman and Kestenbaum — who had rented a car — were asked to go pick someone up from the Krakow airport who had just flown in from Milan. Few other details were given.

“It turns out that the person was the Chabad rabbi of Lviv,” Menachem Mendel Gottlib, Calihman said. “He had dropped off his wife and child in Italy for safety.”

The rabbi wanted to get back to Lviv in Ukraine, “so that the Jews there would have a rabbi there for the Purim holiday, and also so that he could convince them to get out of the city,” Kestenbaum said.

By that time, Gottlib had told them, there was only one rabbi left in the entire city.

They drove Gottlib more than two hours to Poland’s border with Ukraine. There, Calihman, who had her passport, spent more than two hours helping the rabbi travel into the war-torn country.

“I had no phone service for that time,” she said. “And because I was incommunicado, Shabbos was even concerned that I had been detained.”

She wasn’t. Yet, that journey — along with the entire volunteering effort at large — left a strong impression on Calihman, who has a pair of grandparents who were Polish Holocaust survivors.

“It also caused me to reflect a lot on my story of my grandparents, who themselves were refugees from that area, and wound up in Riverdale eventually,” she said. “Watching the outpouring of the entirety of Poland and so many international volunteers, there was a bittersweetness to it because I realized that my grandparents and their families didn’t receive that sort of outpouring of support.”

“At the risk of sounding arrogant, but we’d like to think that we made a very, very, very small difference in the lives of really the dozens of people that we met,” Kestenbaum said, now back home as well.

“It’s a drop in the bucket, because there’s a million of them. But we definitely walked away feeling like we did something. And we also walked away thinking we need to do more. We need to come back.”