Using newspapers, book chronicles early Jewish history

It’s not clear who first coined the phrase “journalism is the first draft of history.” Philip Graham, a former publisher of The Washington Post — and husband of the even more famous Katherine Graham — made it popular in a 1963 London speech. But another Post writer, Alan Barth, published the quote in an editorial about 20 years prior, and it peppered the editorial pages throughout his tenure.

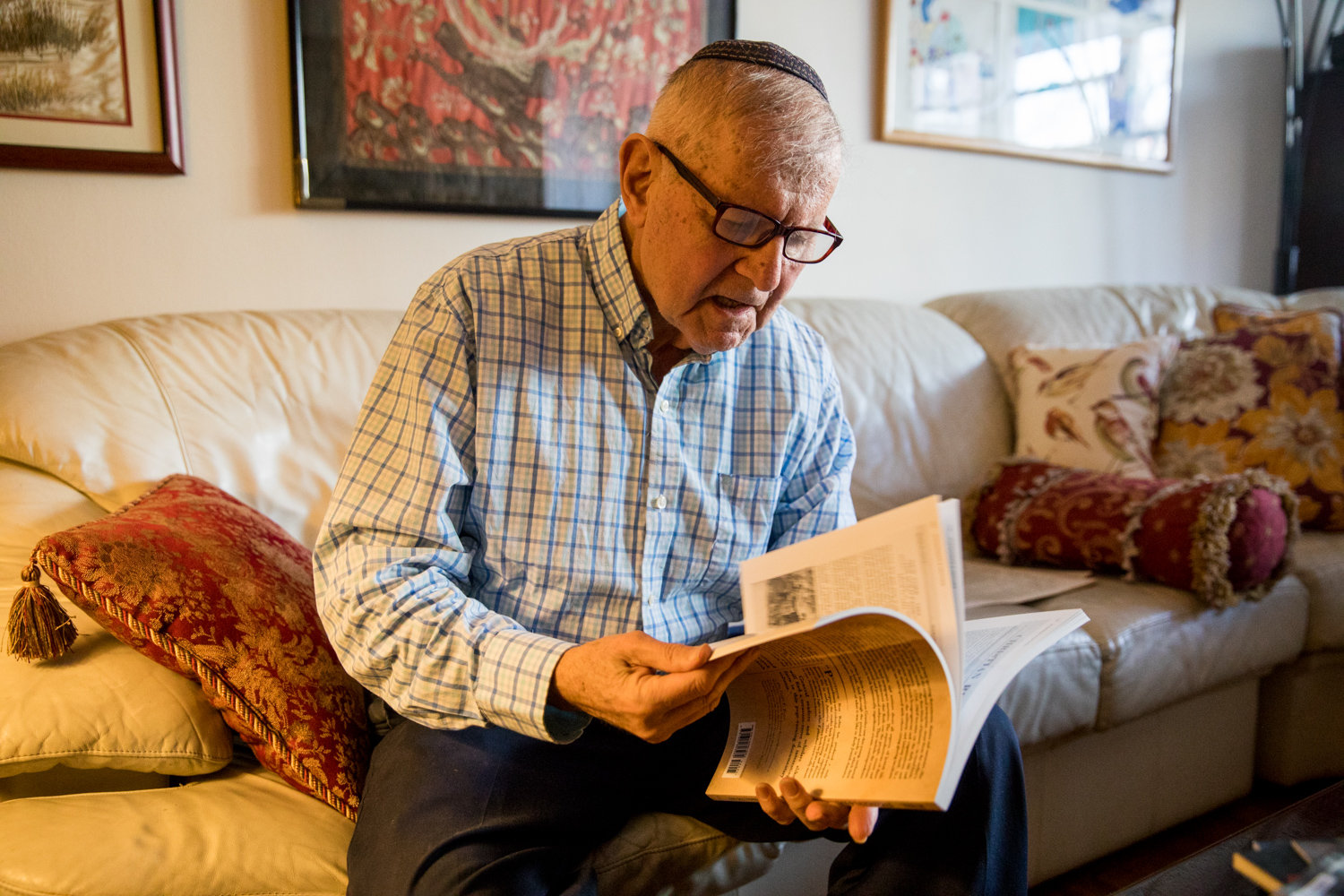

In any case, the person who first coined the saying doesn’t change the truth of it — especially for Ron Rubin, a longtime Bronxite, professor and collector.

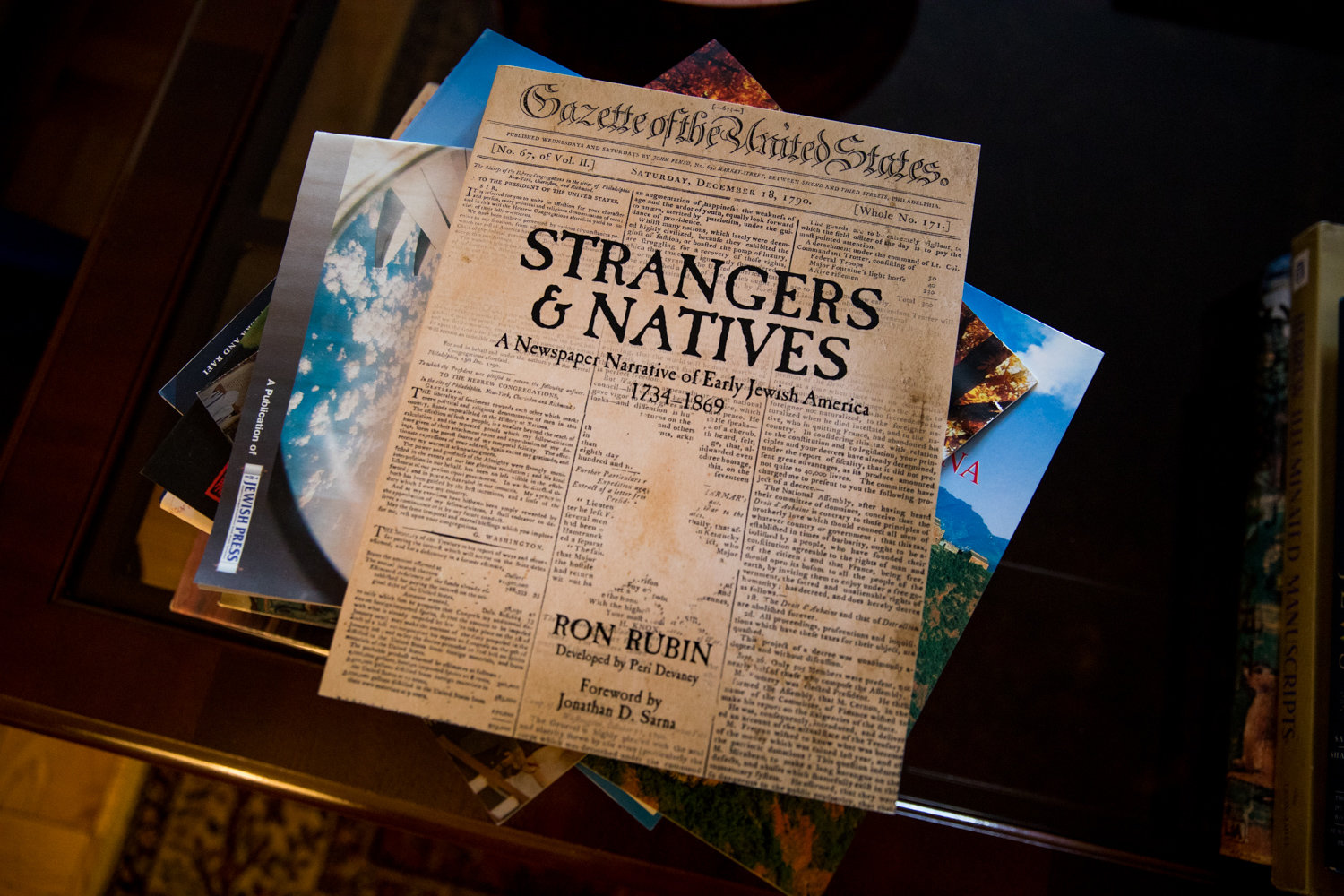

In a new book, “Strangers & Natives: A Newspaper Narrative of Early Jewish America,” Rubin traces American Jewish history from the 1730s to the late 1800s, using only newspapers to guide the way.

“Previous histories of American Jewry are based on diaries and memoirs and biographies,” Rubin said. “None have used exclusively newspapers as a source.”

Rubin is a collector by nature, and was always drawn to finding and filing away important historical moments. His hunt for newspapers that covered his interests took him to New York City’s famous auction houses and to the internet’s most popular auctioneer.

“I just felt like a detective, I pursued what was around,” he said. “There are some dealers who deal with antiquarian newspapers, eBay, and there are auction houses like Sotheby’s, Christie’s — so it’s (an) accumulation of all these things.”

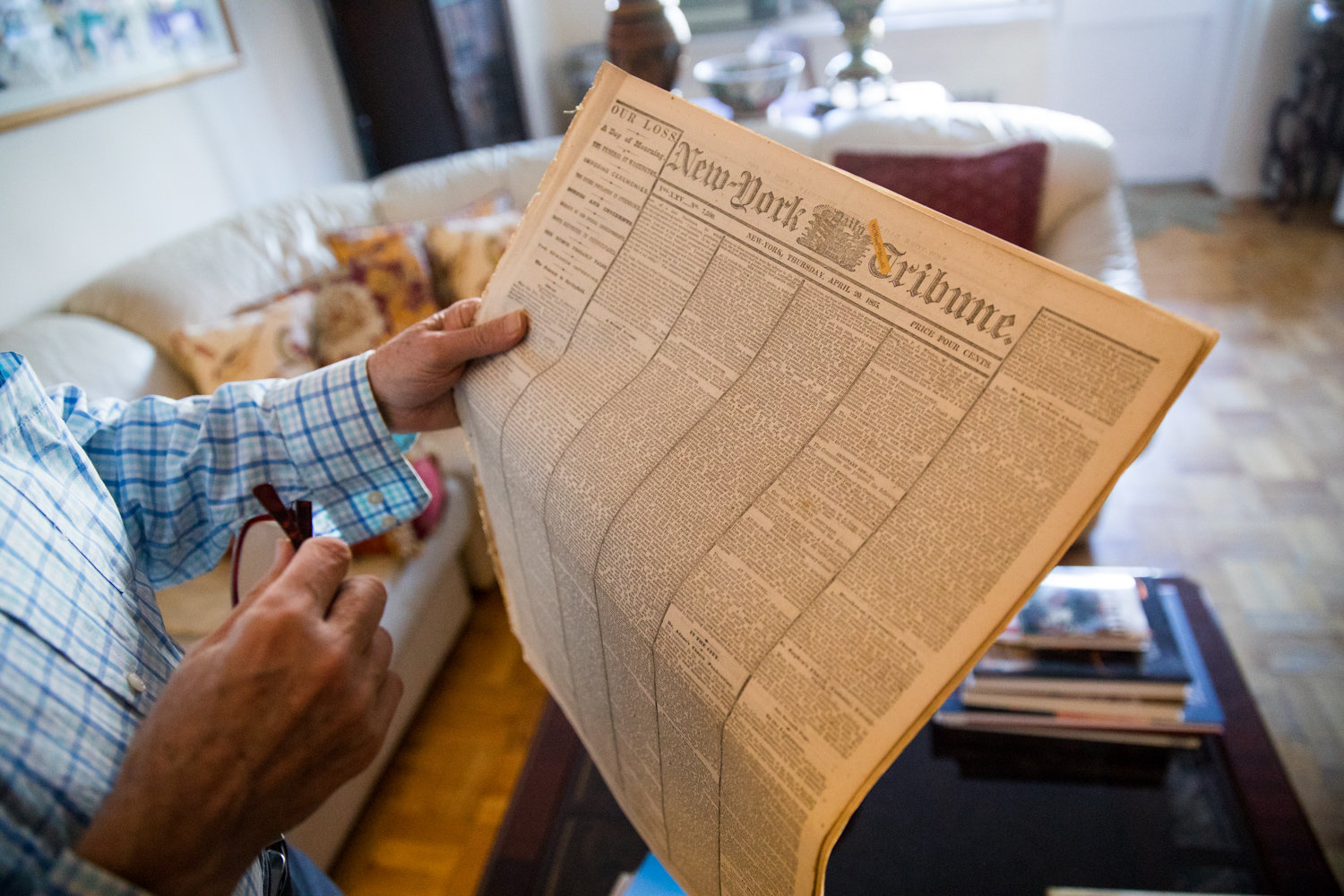

Rubin’s sleuthing has garnered him a collection of carefully preserved newspapers in his Henry Hudson Parkway apartment, most in mint condition and carefully preserved behind a smooth plastic film.

His topic made the search a little more interesting — sometimes, he said, dealers didn’t know the value of the newspapers he bought in Jewish history. There’s one in particular he cites as a hidden gem, unknown to its previous owner: A copy of The New York Weekly Journal published in May 1734 contains what Rubin believes is the first reference to a synagogue in an American newspaper.

A listing for a home on what was then Duke Street says the house is located near the synagogue — Congregation Shearith Israel, the first synagogue to be built on the North American continent, located on what’s now West 70th Street.

“You didn’t have street addresses, numbered street addresses,” Rubin said. “He was trying to sell a plot of land, so what does this show? It shows that the synagogue was notable enough to be a marker point.”

Another article from a New Orleans paper notes the opening of the fifth New York City synagogue, describing the congregation as “wholly of Germans, many of whom have been driven to this country by the illiberal and oppressive laws of the kingdom of Bavaria.”

“In this period, the Jewish population was very small, in the time of Washington,” Rubin said. “There were about 1,000. I think there were maybe 2 or 3 million people here already, so it was always very small.”

That small population making strides to establish themselves in the country inspired the book’s title, Rubin said. As Jewish communities opened businesses, schools and synagogues — despite their comparatively small numbers — they made themselves a home in the United States.

In the Book of Genesis, Abraham searches for a place to bury his first wife, Sarah. When he encounters the Hittites, he pleads with them to grant him a plot.

“He says, ‘I am a stranger and a native among you,’” Rubin said. “It’s directly from the Bible.”

His newspapers are also full of advertisements, Rubin said — another way to trace commercial history.

“The first page would always have ads, the back page had ads, and they would squeeze in news in Pages two and three,” he said. “So the ads reveal a lot.”

Advertisements for Jewish businesses, events, or even a Jewish man advertising a found wallet, show the extent of Jewish involvement in their new communities.

There are also articles that note early American anti-Semitism. An 1869 issue of Manchester, New Hampshire’s The Union Democrat features an article about Ulysses S. Grant’s Order 11, which demanded Jewish people leave their homes in Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee within a day of receiving the order.

According to that article, 2,000 Jewish voters from Missouri signed a petition stating that “none in the 19th century in civilized countries has abused the Jews officially, in broad daylight and most barbarously.”

Despite those instances, Rubin said, Jewish people and communities were largely welcomed by Colonial America, citing Jewish police chiefs, newspaper editors, and even events like a full article describing a “fancy dress ball” hosted by the city’s Purim Association.

In Rubin’s eyes, the advertisements and notifications of deaths, births, and those articles simply alerting the public to new synagogues and events, hold just as much weight as those articles that record Grant’s order, or the first Jewish Americans to be elected to office.

“At this point, I don’t know if I invented the term of newspapers as the first blush of history,” Rubin said. “It’s the first account of things.”