Bill Schleicher, a true social justice warrior from Riverdale, dies at 80

Longtime resident was retired editor of District 37 union's Public Employee Press

It was a little after 4 p.m. on July 1, 1971, when Bill Schleicher walked into the 43rd Street office of The New York Times, carrying a camera and extra rolls of film.

No one seemed to notice at all as Bill walked around The Times’ newsroom and administrative offices, snapping picture after picture. Reporters had their feet propped up on their desks. Several were milling about, sharing the gossip of the day. If life was busy at The Times, it sure didn’t show it, at least to Bill’s camera lens.

All of this happened just weeks after The Times started publishing the Pentagon Papers — the series of internal government documents proving how the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson lied to Congress and the American people about the state of the Vietnam War.

But it wasn’t the Pentagon Papers that drew inquisitive journalist to the offices of The New York Times that day. Instead, it was an editorial the newspaper published a week before claiming that “the prevailing attitude among public employees here seems to be one of how little work they can do for how much more pay,” claiming some city clerks were observed “chatting with each other, settling personal financial accounts, catching up with their newspaper reading, or just daydreaming.”

Bill was a reporter, too. Not for The Times, but for Public Employee Press, a newspaper published by a union now known as American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees District Council 37, that represented those very city workers. Security finally caught up with Bill, and pulled his camera away from him. They popped open the back, grabbed the film, and then exposed the entire roll right in front of him, ruining it.

Security would eventually let Bill go, but they hadn’t stopped him from achieving his goal. Before he was caught, Bill had loaded a dummy roll of film into his camera. The real pictures were locked in a canister in his pocket — and soon it would be on the front page of not only Public Employee Press, but in the pages of just about every other newspaper in the country.

Bill didn’t want to embarrass The Times — it was, after all, his favorite daily newspaper. He simply wanted to prove you could find people goofing off in any office anywhere at any time — and it wasn’t exclusive to city workers.

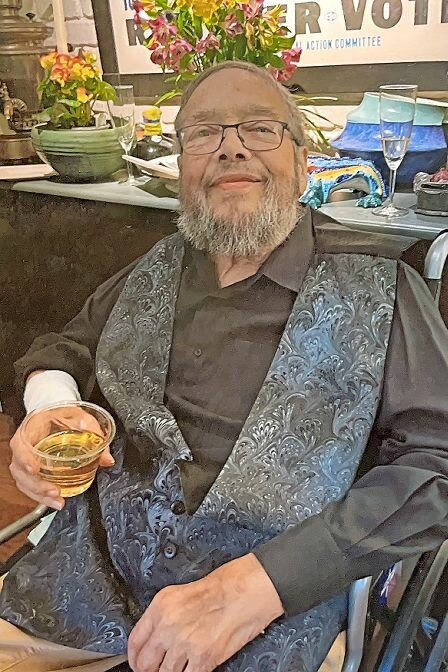

It was the beginning of a long, storied career for Bill Schleicher and the DC37 newspaper that ended in his retirement in 2015. Bill died on Sunday, Aug. 20, at his home on Ploughman’s Bush, after a lengthy illness. He was 80.

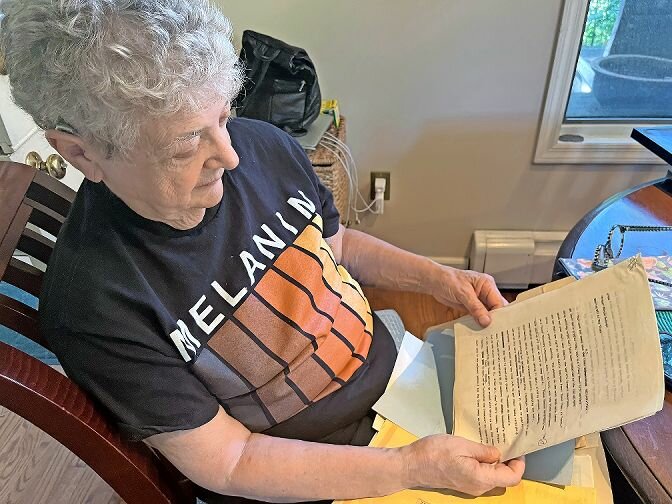

“That’s exactly how people remember him,” said Ellen Chapnick, Bill’s wife of 40 years. “They remember what a tireless fighter he was for social justice, especially labor rights. How everybody was important to him. Nobody’s just their job. Everybody’s a human being. And I think that’s part of why he was so good at his job.”

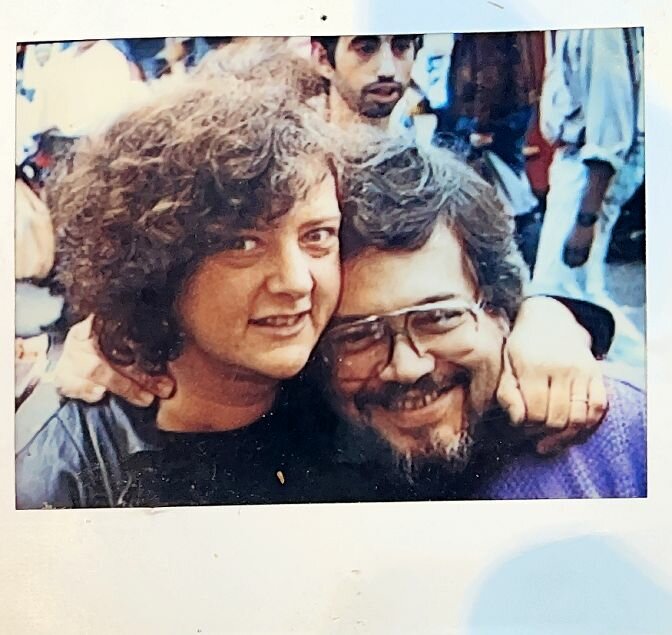

Ellen met Bill on her first day working for the union in 1978. By then, Bill was overseeing new hires, meaning he would have to talk to this young lawyer wearing a pink pantsuit, her skin unusually red.

“Bill says at some point, ‘You know, I can’t help but notice you’re a little sunburned,” Ellen says. “I didn’t think it’d be a good thing to say, ‘Well, I was committing an act of civil disobedience just two days ago.’”

Ellen had been in Puerto Rico supporting efforts there to block U.S. Navy drill maneuvers there by local fishermen who claimed the sessions were destroying their livelihoods.

It ended up being a very short conversation, with neither impressed with each other, and Ellen deciding to nickname him “Skippy” since she didn’t think he was so bright.

A year later, Ellen found herself heading to Puerto Rico full-time, and she feared leaving her department in bad shape. So, she was told to talk to Skippy — something she was hardly looking forward to.

“I invited him out to lunch,” Ellen recalls. “Those days, City Hall park didn’t have a huge fence around it. So, you could picnic on the grounds. What was supposed to be a 30-minute discussion went three hours. And the rest is history.”

The two were married in 1984 after Ellen returned to New York, and they settled in Brooklyn, where Bill could be close to his sons Erico and David. But it was also a time when illegal drugs ruled the streets, and the family home was smack-dab in the middle of a drug transportation route.

Bill loved urban life, but Ellen was looking for something far more peaceful. Erico and David were heading to Ethical Culture Fieldston’s upper school, so Riverdale looked mighty attractive. And when Ellen first laid eyes on that house for sale on Ploughman’s Bush off West 247th Street, she knew she felt at home.

There, Bill and Ellen lived very busy lives — Bill with Public Employee Press as its editor-in-chief, and Ellen with her teaching, legal work and advocacy. Still, they would find time to enjoy their passions. For Bill, it was fishing and it was grilling in his backyard — a hobby that was more art for him.

“As long as Bill could barbecue, he was happy,” Ellen said. “He was really a master at it. I mean, he made incredible steaks — I never had a steak in a restaurant that was anywhere near his anywhere.”

Their love of food would take them to some of New York’s finest restaurants. But their favorite stop — when not getting sushi in Greenwich Village — was Tobalá on Riverdale Avenue.

“Bill was in the hospital for about three months, and sometimes I just couldn’t bear to come home,” Ellen said.

“So, I would go over to Tobalá. They were never improperly curious, but they knew something was going on. One of the maître d’s once told me the only question is whether you or your margarita on the house is going to get to your table first.”

In his final months, Bill wanted to be clear everyone knew how much he and Ellen loved each other, so they hosted a vow renewal in their home, finding a way to fit 40 people into their dining room.

The ceremony was led by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, a longtime friend of Ellen’s from her days as a Bronx judge, who insisted she be the one to lead the ceremony.

“Why does this marriage work?” Sotomayor told those who gathered on that beautiful May day. “The answer is relatively simple. They’re both passionate about helping people at large, and bettering this country and the way it treats the disadvantaged.”

And it describes perfectly who Bill Schleicher was.

“People have been sending us emails, writing that they’re sorry to for our loss,” Ellen said. “But they’re also sorry the world lost one of the great all-time, funny curmudgeons.

“He fought for social justice because he had a big picture of you. He understood the individuals that make up our society — low-income people, people of color, women. Everything he did, it was never a theoretical thing for him. It’s real. It’s a real thing on the human level for him.”

William Schleicher was born Nov. 6, 1942, and is survived by wife Ellen, sons Erico (Kim Kelsey) and David (Amanda Kosonen), and grandchildren Miri, Charlie and Nate.