Can Albany heal Bronx’s housing court woes?

Coalition calls for $172M statewide bill to expand and strengthen Right to Counsel

Renters in Albany — they’re just like us. And the New York City Right to Counsel Coalition says they need access to lawyers in housing court, too.

Nikkiea Philpot had just moved into an apartment on West Lawrence Street in Albany’s Pine Hill neighborhood when she discovered that her home had no heat. Rather than wait for repairs, she took her landlord to court to ask for her deposit back.

The battle dragged on for months while she and her son, who is asthmatic, doubled up with family.

Following a judge’s instructions, she gathered evidence and brought it to the courthouse on a thumb drive, determined to prove her case even without the help of a lawyer.

“I had my evidence written down and I won that case,” Philpot triumphantly told the crowd gathered at Albany City Hall Monday. They had traveled from across the state to rally for the right to counsel in New York when tenants face off against landlords in housing court.

After all that, Philpot said, “they gave me my security deposit back. But I still had to find another place to live.”

The coalition of lawyers and tenant leaders that fought and won the country’s first Right to Counsel law establishing universal access to free legal services for low-income tenants in New York City five years ago are taking their bid to Albany.

“I don’t like to make predictions, but I definitely hope that we can get this done this year,” said Assemblyman Jeffrey Dinowitz, a co-sponsor of the state bill.

A promising start

In 2018, when New York City’s fledgling Right to Counsel program had been rolled out in only 15 city ZIP codes, citywide housing court supervising judge Jean Schneider praised its success. In testimony before a state hearing on access to legal services in New York civil courts, she said the backlog of cases some judges had warned of was so far failing to materialize.

In fact, Schneider said, “our court is improving by leaps and bounds.”

Landlord attorneys were no longer accosting tenants in the hallways to talk about signing a stipulation, she said. The practice had been common in New York City housing courts in the days before Right to Counsel, when fewer than 1 percent of tenants had a lawyer compared to 95 percent of landlords.

New York Court of Appeals Acting Chief Judge Anthony Cannataro, who was the administrative judge of city’s civil court cases in 2018, chimed in to say cases were actually reaching settlements faster, and judges wasted less time explaining court procedures to rattled tenants.

The program’s early success belies what happened this year. When the eviction moratorium ended in January, the city’s housing courts exploded with activity. The city’s courts suddenly had nearly 200,000 active eviction cases on their hands, including 144,000 eviction filings that were paused at the start of the pandemic and another 46,000 filed during the moratorium. New York City landlords have initiated another 97,000 eviction cases so far this year.

Nonprofit law firms contracted with the city’s civil justice office to provide free counsel to tenants could not keep up. In March, that office instructed them to report a daily list of cases they cannot take on. Meanwhile, the court administration directed housing court judges to proceed with cases even when eligible tenants are denied access to a lawyer.

Despite the benefits of expanded access to legal services, court spokesperson Lucian Chalfen told The Riverdale Press “the legal services providers have never given us any indication as to when they would be able to represent everyone who is eligible.”

“Without such a date, they are in effect asking us to adjourn cases indefinitely, which is not going to happen,” he said, adding that there is an “ongoing dialogue” with lawyers and the civil justice office.

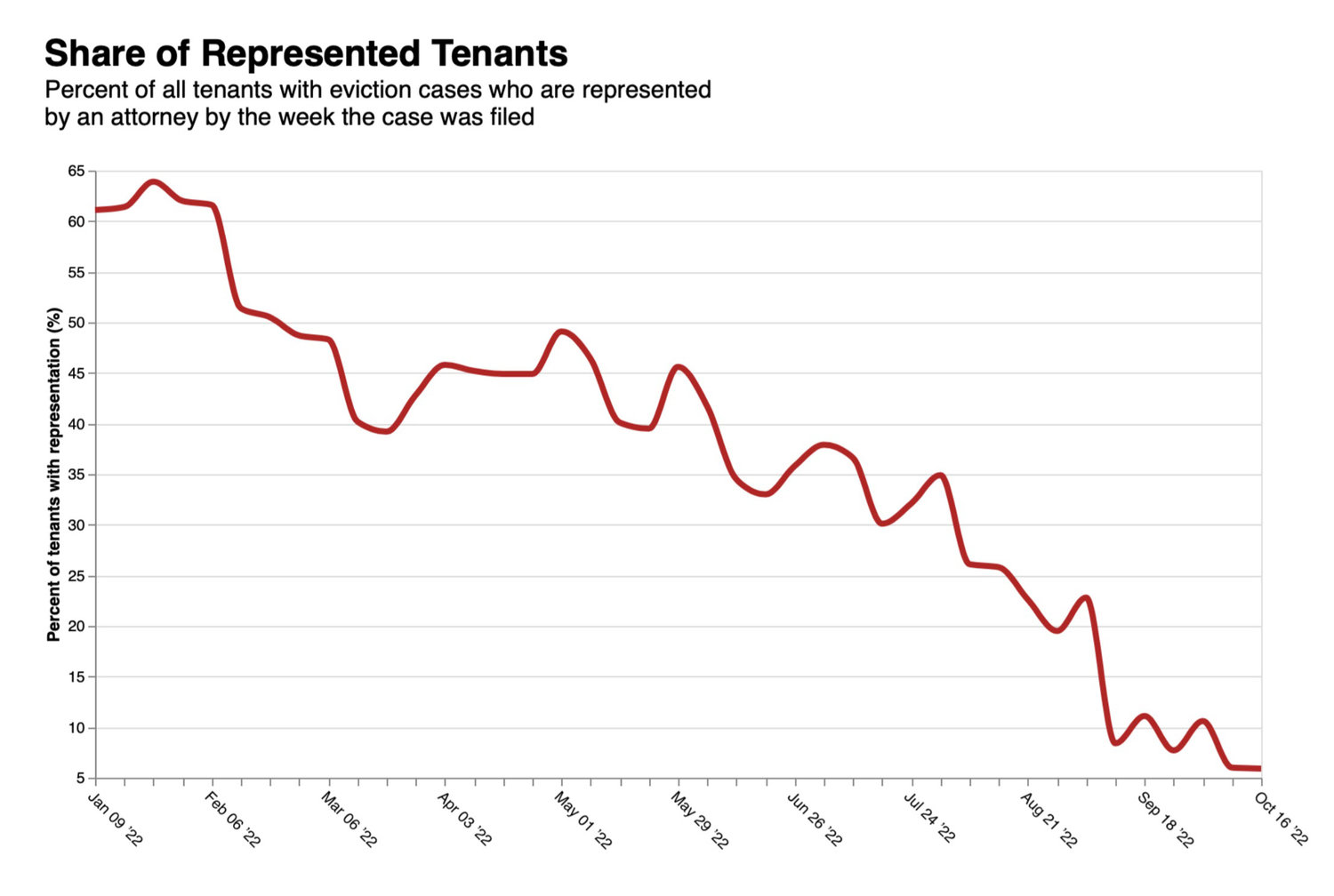

Until a few weeks ago, a precise tally of those falling through the cracks evaded public scrutiny. That changed when data analysts at the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development and the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition released their live eviction crisis monitor, a tool that taps into statewide court data to show the rate of representation in tenants facing eviction. It took four years to create, said ANHD’s Lucy Block.

The rate plummeted into the single digits this fall, with less than 6 percent of tenants gaining access to a lawyer in the most recent week of data ending Oct. 22. The data include all residential eviction cases with one additional court appearance after initial intake, the crucial juncture where Right to Counsel providers screen tenants for eligibility. If a tenant gains a lawyer a few weeks into their case, the tool is automatically updated to reflect the change.

Only 39 percent of tenants who have faced eviction this year have had a lawyer, the analysts found.

The court administration’s own records, which it began to keep in March, indicate 48 percent of eligible tenants are represented in eviction cases, Chalfen told The Press. He did not challenge the most recent figures reported in the Eviction Crisis Monitor.

Taking away the judge’s discretion to adjourn based on the facts of the case, Chalfen said, could lead to “inequitable results.”

But that’s exactly what advocates are asking lawmakers to do in Albany next year.

A bigger, better

Right to Counsel

Legislation establishing a statewide Right to Counsel program passed the New York Assembly in June this year but died on the state Senate floor. The assembly bill is now headed for a reboot in the Judiciary Committee, and tenants meanwhile have already kicked off their campaign to pass it. Their bill would allocate $172 million in the fiscal year 2024 budget to implement the proposed statewide initiative.

But they have some revisions in mind.

The Right to Counsel NYC Coalition, which ran a well-organized campaign to pass New York City’s Right to Counsel Law in 2017, is taking this year’s lessons to heart. A new draft of the state bill will include stronger mandates for courts to inform tenants of their rights and adjourn cases until eligible tenants are able to retain a lawyer, limiting the broad discretion judges have so far held in New York City housing courts.

“We negotiated a lot out of the (state) bill last session,” said the Coalition’s campaign manager, Katy Lesell. “We have to do a lot of planning in December. We’re planning to be in Albany. We’re increasing our efforts to visit the courts.”

“It’s good for the judges to know they’re being watched,” she said. “There’s an unbelievable amount of daily injustice. Every day we’re disrupting conversations between landlords' lawyers and tenants in the halls.”

An analysis by Stout Risius Ross consultants estimated that a statewide version of Right to Counsel would cost between $144 million and $200 million annually and would provide free legal representation to an additional 46,600 households outside of New York City each year. Such a program stands to decrease eviction filings outside of New York City by 19 percent, the study predicted.

“As we fight to expand Right to Counsel, we’re also sending a message to the courts that we need to uphold the law in New York City,” said Right to Counsel NYC Coalition coordinator Susanna Blankley.

About 100 people attended Monday’s rally at Albany’s City Hall. They arrived on buses from New York City and Westchester, others from even further afield. A few in the crowd were from Rochester.

“Landlords overwhelmingly have access to legal counsel, and it’s only reasonable to ensure a level playing field when dealing with basic human needs such as housing,” said Dinowitz.

Did he have a message for the protesters?

“Keep up the good work,” he said. “We need to grow support, especially in the state senate, and get this bill over the finish line.”

Abigail Nehring is a corps member with Report for America, a national service program that places journalists into local newsrooms.