A quiet giant, hiding in North Riverdale history

As the original twin towers of the World Trade Center rose out of Manhattan’s Financial District, a second set of twin towers had climbed into the sky 15 miles up the Hudson River, casting its own shadow over North Riverdale.

A common builder linked the two together — Tishman Realty and Construction Co. — yet these two construction projects couldn’t be more different. One would become a symbol of freedom in the aftermath of Sept. 11, 2001. The other wouldn’t be remembered as two towers at all. Instead, the 220-foot elevator shafts and support columns were enveloped by 20 stories of what transformed into a nearly self-contained community where Mosholu Avenue and West 255th Street meet. It’s become known as the Russian Mission.

The white behemoth is a landmark itself, visible from miles away. It’s surrounded by gates and security so tight, one might imagine Vladimir Putin himself resided there.

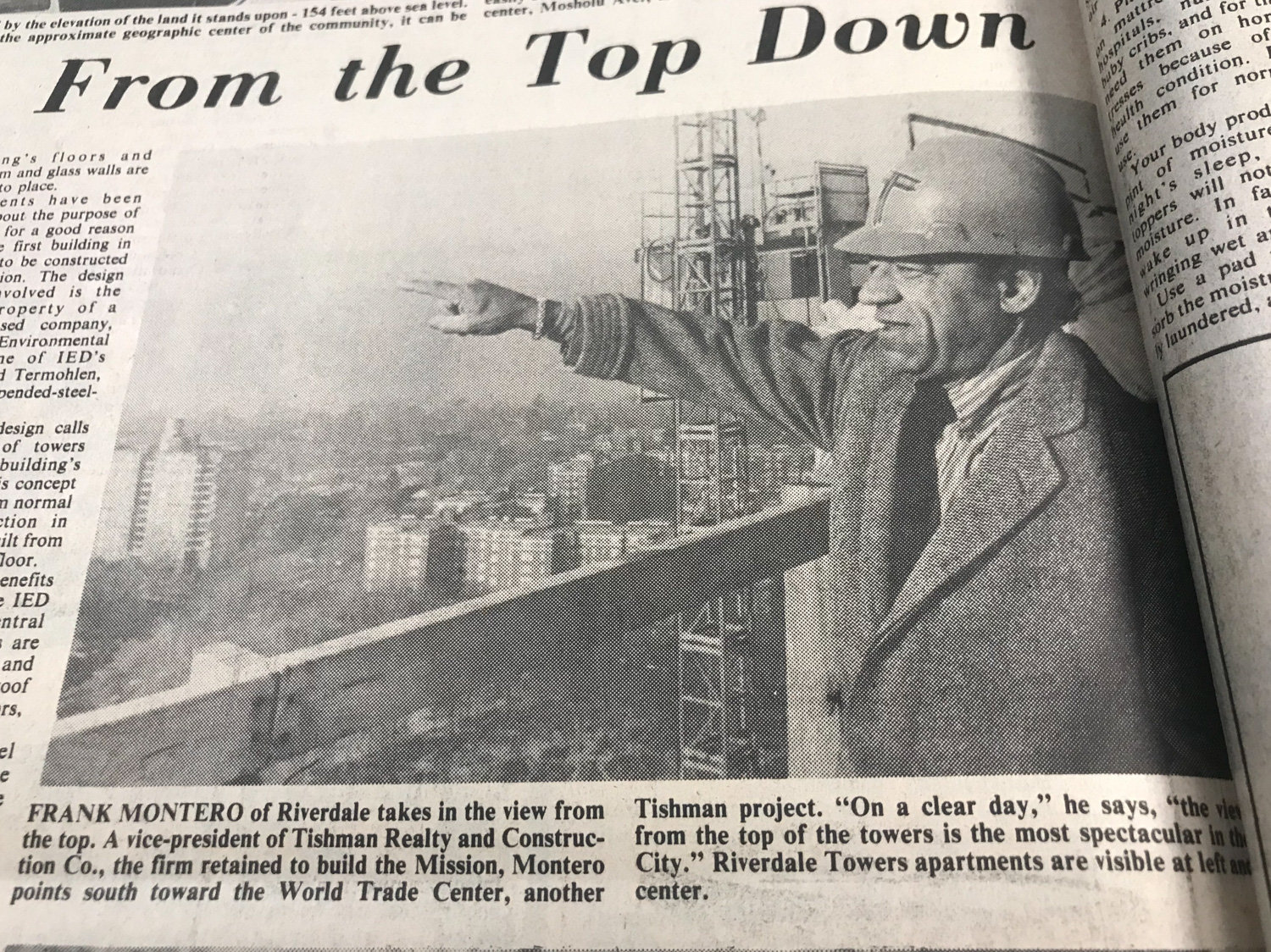

But on a chilly February day in 1974, when the mission was nothing more than these two massive concrete towers in the middle of what was once known as Faraday Woods, a single American flag fluttered in the wind so high above the community. It was joined by Frank Montero, a major political figure in Riverdale at the time, who also happened to be a Tishman vice president.

“On a clear day, the view from the top of the towers is the most spectacular in the city,” Montero told then Riverdale Press features reporter Sol Solomon, who would become one of few Americans to set foot on the property.

Within weeks, the real construction would begin. But not here. Instead, each of the 20 floors was fabricated elsewhere, arriving in North Riverdale completely finished. Once here, beginning with the top floor, each would be lifted to the top of the support towers, literally constructing the building from the top down.

The top-down technique was patented by International Environmental Dynamics, which played a role in the construction of about a half-dozen mid-sized towers, mostly in California, before going out of business itself.

The technique had a couple of great benefits for the Soviet government at the time. First, it didn’t require a steel beam framework, meaning architects could literally design floorplans on a completely blank canvas, eventually opting for 15 apartment units per story. But even better, it allowed each floor to be constructed off-site — far less chance any American intelligence agency could infiltrate it with listening devices.

This was right smack dab in the middle of the Cold War, after all.

The land itself was controversial even before the Soviet Union arrived. It was owned by Robert Weinberg, a prominent architect behind the nearby Vinmont Houses project, an affordable housing project where tenants would maintain their own yards and units. Weinberg originally tried to build 340 low-income apartments on the site in the late 1960s, part of Mayor John Lindsay’s “scatter-site” public housing plan, according to a report published by Lehman College’s David Bady.

Neighbors protested, and Lindsay withdrew the project. The land remained vacant until a buyer with much deeper pockets arrived. The USSR was quite interested in the land, however, as a residence for diplomatic families assigned to the United Nations. In December 1971, Weinberg closed the land sale at $900,000 — about $5.8 million today.

Montero expected the building would be ready for move-ins by some 200 families early the next year, but had hoped workers might actually get done ahead of schedule — like before the end of 1974.

Instead, Ambassador Yakov Malik welcomed 80 neighbors inside the compound at the end of April 1975, calling the completed project the “first child of the cooperation between the USSR and the U.S.”

In fact, Malik pointed out this wasn’t the first time the two countries worked together. He noted that it was the 30th anniversary “of our victory over fascism,” where not only Adolf Hitler committed suicide as Nazi Germany fell, but also a few days before when American and Soviet troops met at Germany’s Elbe River in the heart of the Reich.

“The Nazis’ plan was to take over, and the Slavic people would have become slaves,” Malik said. “After the Slavs, the other nations would have been enslaved.”

Despite its dominating presence in the North Riverdale landscape, the Russian Mission has remained a quiet neighbor. It’s survived the remaining years of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union, invasion of neighboring countries, lukewarm relations with the United States, followed by cool relations with the United States, and even Barack Obama’s purge of Russian diplomats in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election.

Yet, from time to time, the Russian Mission will become a topic of conversation, like it did this past week when windows on various floors were lit up, creating a 200-foot tall “75.”

What could that mean? Maybe it was the Russian Mission’s celebration of its 45th anniversary, officially opening in 1975? Or more likely, it’s the same celebration Malik put together at the very beginning of its existence — the fall of fascism, allowing countries like the United States and Russia to exist freely, whether those relations are friendly or not.

At least for one night in 1975, everyone was friends no matter what flag they stood under.

“The historical facts of war we will never forget,” Ambassador Malik said. “That’s why we hate war at the utmost. We don’t close our eyes that there are enemies against our détente with the U.S. We hope sense will overcome these enemies.”

CLARIFICATION: The Russian Mission building, more formally known as the Russian Diplomatic Compound, had most, if not all, of its floors constructed on-site before being lifted to construct the 20-story building from the top down. A story in the May 14 edition surmised floors were built off-site as to prevent American intelligence “hacking.” At least one person familiar with the building at the time of its construction has suggested some aspects of the tower may have been fabricated off-site, but it’s not clear how much of it — if any — was assembled somewhere other than Faraday Woods.