Reps demand MTA halt plans eliminating cash fares

Transit advocates say policy could disenfranchise lower-income passengers

It’s been a little more than two years since the Metropolitan Transportation Authority stopped taking coins on its express buses, relegating riders to MetroCards or using the MTA’s touchless OMNY payment system.

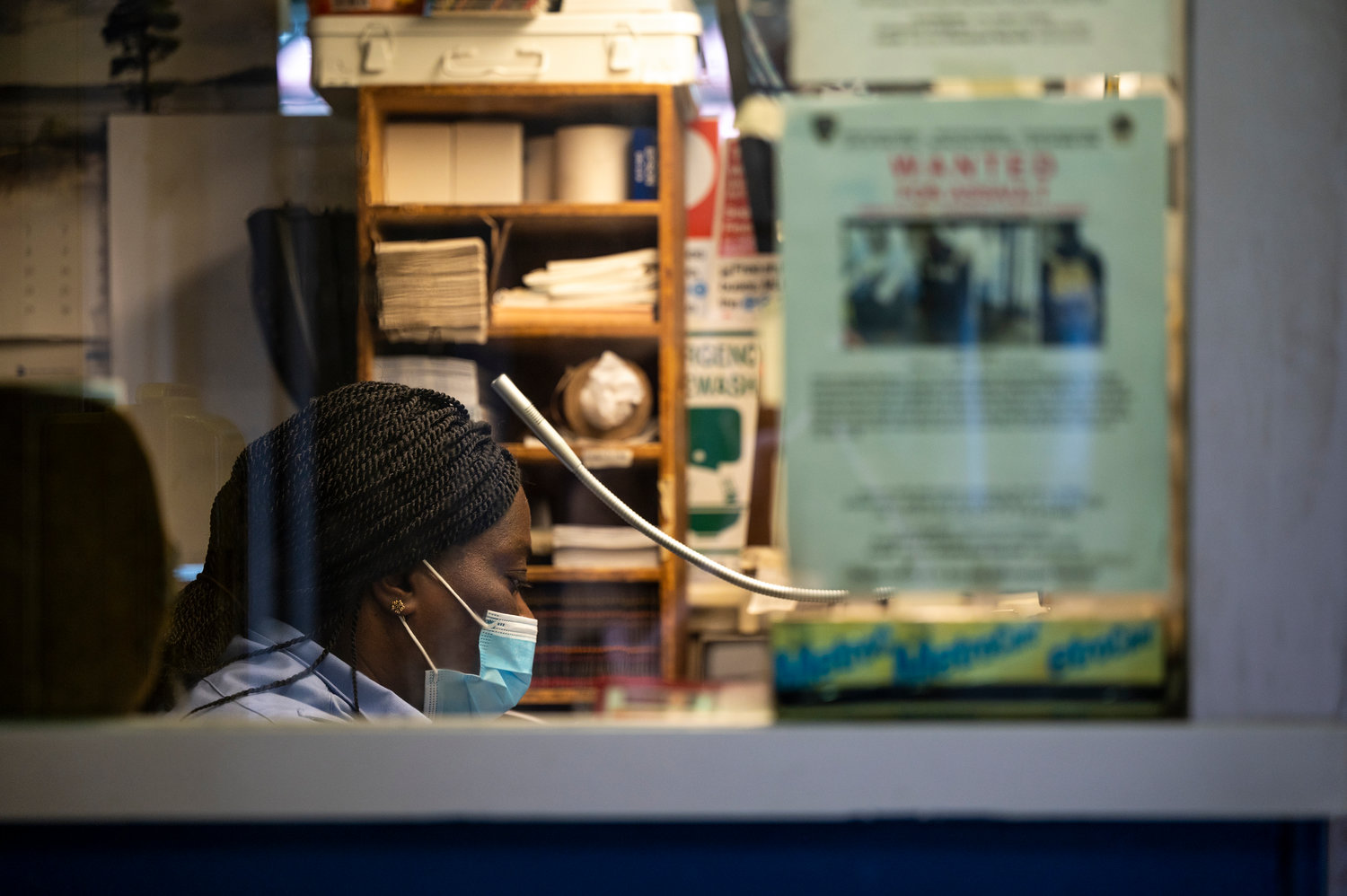

Now the MTA is set to not only remove cash from subway stations, but agents — who generally help straphangers purchase MetroCards, answer questions or handle problems — as well.

Except the authority might have a fight on its hands. State legislators have joined with the transit workers union calling on the MTA to keep the agents, and keep the cash.

“Why take the (cash) option away?” asked Mike Smith, a regular commuter who was recently found waiting for the bus at West 236th Street.

“Sometimes your card doesn’t go through, so you go over to an agent. Am I supposed to not go to work or jump the turnstile?”

The MTA already has had a trial run eliminating cash, of sorts, thanks to COVID-19. At the height of the pandemic, the state agency shut down cash operations in many of the city’s more than 450 subway stations, as well as on its commuter rail system. Once traveling and people interacting with each other became safer, cash and agents were restored. At least for the most part.

“After a year of record ridership lows, the MTA should pull out all the stops to welcome riders back on board,” said Jay Cohen, director of the New York Public Interest Research Group’s straphangers campaign, in a release.

At the height of the pandemic, MTA ridership dropped from 5.5 million riders daily to just 2 million, the agency said — much of those numbers coming toward the end of 2020 when passengers felt more comfortable returning to enclosed environments. Yet, even now, the MTA is managing just 3.5 million riders, even on its best days.

For some, using the subway system is not easy. Some morning commuters have trouble working the automated MetroCard vending machines — that is, when they are working. Local stores sometimes sell out of their own MetroCard stock, leaving many to depend either on using a bankcard or smartphone with an OMNY display, or paying in cash.

When those problems occur, it’s station agents that save the day, says Manhattan state Sen. Brian Kavanagh.

“They provide public information and directions, especially when often-confusing service changes are in effect,” the senator said, in a release. “They offer an extra layer of security to a system that often reminds us that if we see something, we should say something.”

Station agents also help disabled riders without having them roam the platform, and can even take questions from commuters who don’t speak a lot of English, or who are simply confused by the world’s largest mass transit system.

If the MTA follows through on eliminating these agents, it would come at a time when the pandemic already has eliminated many jobs in working-class communities, according to state Sen. James Sanders Jr., who represents the greater Jamaica area of Queens.

“I stand with transit workers who have been at the forefront of making our city and state function through this pandemic,” he said, “sometimes at the cost of their own lives and health.”

The MTA says more than 150 of its workers died from complications related to COVID-19.

Even worse, it could further widen transportation disparities between low- and high-income communities.

“By eliminating station agents, the MTA is limiting public transit access for thousands of New Yorkers,” state Sen. Gustavo Rivera said, “especially in low-income communities who rely on these booths, given that they may not have access to a credit card or a cell phone to purchase their MetroCard.”

The subway station at Broadway and West 231st Street already lacks a station agent. If the MTA’s transition to cashless sales goes into effect, commuters will need a debit or credit card to purchase a MetroCard from vending machines.

But is the MTA listening? Perhaps.

State Sen. Julia Salazar, who represents parts of Brooklyn that includes Bushwick, says she’s hearing “overwhelming support for the MTA to reverse their policy.”

The MTA, however, simply says that “no decision has been made,” and in the meantime, continues to accept cash nearly everywhere it did before the pandemic.

“As we have said repeatedly, the MTA is evaluating options and communicating with our labor partners to determine the best outcome for our customers,” the agency said, in a statement.

Losing cash on New York City’s transit system is bad enough for Transit Workers Union Local 100 president Tony Utano. Finding there are no more station agents could be a nightmare.

“Where do you go when someone gets pushed on the tracks, or some crime is being committed? Or a person needs to know where they got to go?” Utano asked during an Aug. 10 news conference. “There’s nobody there.

“We need congress, we need the Senate, we need people to step up and tell the MTA (to) give the citizens of New York City the customer service they need.”